The clean, elegant lines of Waterloo Bridge stretching across the River Thames from Victoria Embankment to Southbank, surprise visitors by their stark contrast to some of the more elaborately decorated bridges in central London. Its Portland stone cladding is striking in sunshine, and when it’s washed by rainfall it releases chemicals that keep it more or less clean. Opened in December 1945, it replaced the much admired orignal bridge, destabilised by the stronger tidal flows after the opening of the new London Bridge downstream in 1831.

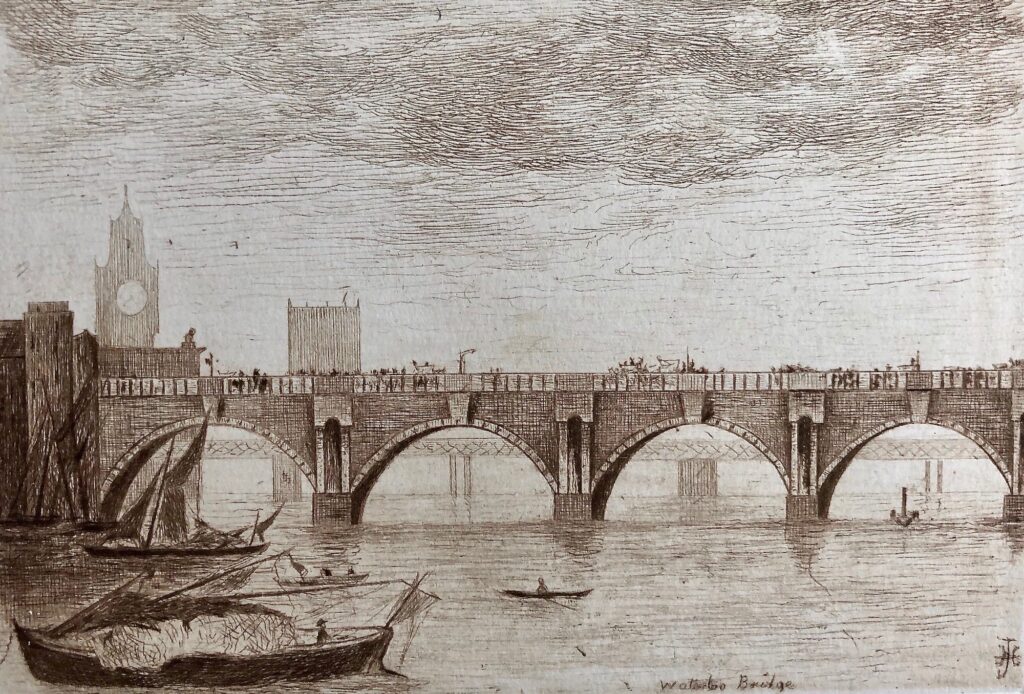

Artist J.H. Herring wrote of the original bridge in Thames Bridges from London to Hampton Court, 1884, that “Waterloo Bridge, from its lightness, grace, and symmetry of structure, [is] perhaps the noblest bridge in the world.” Initially named “The Strand Bridge” when the Public Company to finance it was first set up by an Act of Parliament in 1809, the bridge was renamed “Waterloo” in 1816 in honour of that “great battle”. Looking at the present bridge with the simplicity and elegance of its structure, built not after but during the bombings of the Second World War, it seems a worthy successor.

The old Waterloo Bridge, designed by John Rennie, was opened by the Prince Regent in June 1817, accompanied by the Duke of York and most fittingly, the Duke of Wellington. The bridge was lined by veterans of the conflict, which might possibly have included my great, great, great, grandfather, who fought at the battle of Waterloo. It was universally admired. And particularly by artists including Constable and Italian sculptor Canova. Later it was to feature in the works of Whistler, Monet and marine artist William L. Wyllie. In 1905 Wyllie and his wife Marion published London to the Nore, an account of their journey downstream from Westminster to the Thames Estuary. It was illustrated by William Wyllie with engaging descriptions by Marion, and she had a few things to say about Waterloo Bridge.

While her husband was working, she enjoyed watching passing river traffic, and from Waterloo Bridge, she observes: “Up with the tide drifts the dumb barge Emma 257, with a cargo of tarred-wood blocks. Two men are in charge; but it is only now and then that, with a slow long pull, they keep way on her. […] The Scorcher with six in tow full of coal, passes sedately. The next is an up-river tow, the barges being of a different shape, smaller, and cut low, so as to be able to pass under any bridge.” Then she turns to a dark side of the bridges’ history.

“Having gone to Waterloo Bridge – called by Hood the Bridge of Sighs – I was leaning on the parapet watching the barges being towed under one of the arches, when the caretaker, a man I know, came up with a civil “Good-day, ma’am!” What he does not know about this stretch of the river is not worth knowing…” She goes on to mention that the caretaker was “a little disappointed, on one occasion, that the Master (William Wyllie) could not take in both sides of the river, so as to incorporate the Houses of Parliament and St. Thomas’s Hospital in one picture.” However, he then continues, telling her of the numerous tragic cases of suicide here with a particular instance of a woman “who had pawned her husband’s clothes and got into disgrace. […] The police-boat got hold of her, and whether she came too or not I don’t exactly know.”

Thomas Hood, mentioned by Marion Wyllie, was the son of a London bookseller, a journalist and poet well-known for his humorous writing but perhaps now best known for his later poems challenging the deprivation and inequalities of the time. Among them was ‘The Bridge of Sighs’ written in 1844, about a young woman jumping to her death from Waterloo Bridge. The poem and the reputation of suicides here was clearly familiar to Marion Wyllie, prompting her questions on the subject and the sad reply that such tragedies were still familiar then, as they are unfortunately today.

The writer of The History of London explains that “Waterloo Bridge gained a reputation for deaths of various kinds.” A case in point was the death of Samuel Gilbert Scott, an American daredevil famous for jumping or diving off all kinds of tall structures or natural features. He came to England in 1837 and after a variety of stunts all over the country, in 1842 he set up a scaffold on Waterloo Bridge from which he was apparently to hang, playing dead, over the river and after a while to break free. However, the noose slipped but the watching crowds thought this was part of the act. By the time the danger was realised, it was too late and despite efforts to revive him, he had died.

And so to the present Waterloo Bridge designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott that replaced the original. Things began to go wrong with Rennie’s bridge when his new London Bridge, opened further downstream in 1831, increased the tidal flow, which gradually affected the structure. Expensive repairs were carried out in the 1880s, and, in 1923 a “settlement in the pier on the Lambeth side of the centre arch and certain subsidences in the parapet and carriageway gave warning that all was not well with Rennie’s masterpiece.” As explained in the programme of the Opening of Waterloo Bridge, the condition of Rennie’s bridge worsened rapidly and was closed to traffic in 1924. There followed years of discussion and disagreement but eventually the decision was taken in 1934 to demolish the old bridge and to build a new one. And, “As a visible sign of this decision Herbert Morrison, then Leader of the London County Council, lifted the first stone on 20th June, 1934.” Actually, according to Peter Mandelson, his grandson, he wore leather gloves and wielded, to great effect, a “mighty great hammer”, a symbolic gesture marking the success of his long-fought campaign to replace Rennie’s bridge. Demolition began soon afterwards and in 1936 Parliament finally gave the London County Council the authority to borrow the necessary funds for the new bridge. By 1939 work was underway but so too began the Second World War.

The Ladies’ Bridge

If you take a sightseeing trip along the central London Thames with a tour guide commentary, you will hear Waterloo Bridge referred to as “The Ladies’ Bridge”.

At its official opening by the then Deputy Prime Minister Herbert Morrison on December 10th, 1945, he praised the workforce: “The men who built Waterloo Bridge are fortunate men. They know that although their names may be forgotten, their work will be a pride and use to London for many generations to come.” But just as their names were destined to be forgotten, a whole swathe of the workforce received no mention at all: the women who worked on the bridge throughout the Second World War. And it was only in 2015, that historian Christine Wall and filmmakers Karen Livesey and Jo Wiser were inspired to search for the truth behind the long-established boat tour guides’ commentary scripts, which told visitors of the “Ladies’ Bridge” nickname for Waterloo Bridge. The result was their film The Ladies’ Bridge Documentary.

After appeals in the press and on BBC Radio London, hard evidence began to emerge of the women who had worked on the bridge. Betty Lind, daughter of

Peter Lind, whose company built the new bridge says she was taken there “when things were quiet” and remembers seeing women at work. David Church, whose father was a crane driver on the bridge, says “there were lots of them…ladies in blue overalls, all in one […] Quite a few hundred ladies up there.”It has been suggested that the lack of recognition of women’s contribution to the building of the new bridge was due to a “likely combination of wartime censorship and loss of official records” when the Peter Lind company went into liquidation. And yet their story has been, for many years, part of the Thames tourist itinerary, though despite having asked a number of Thames friends, I have been unable to trace its origin. Rob Jeffries said “It would not surprise me if it was invented by an enterprising Waterman….and it just stuck!” And until we know better…

Waterloo bridge was undoubtedly a dangerous place to work on during the war. This was underlined in the programme for the Opening of Waterloo Bridge, December 10th, 1945. “At the outbreak of war the superstructure of the bridge was resting on timber supports and was a danger under war conditions, as its collapse would have blocked the river.” Priority was therefore given to the reinforcement of the structure to prevent this. Despite being considered a work of “national importance”, there were “difficulties of supply of labour and materials” and as we now know, the supply of labour was provided by the recruitment of women to fill the gaps left by men who had been conscripted to fight. According to the Ladies’ Bridge Documentary “At the outbreak of war there were 500 men working on the bridge but very soon after, only 150 remained.” Waterloo Bridge was the only London bridge directly bombed during World War II so conditions for workers there were precarious and tough. “There were over twenty air-raid ‘incidents’ on the bridge, causing damage to permanent work and to the temporary bridge, and destroying some of the contractor’s plant and material.” The most serious incident was on May 10, 1941, when a “high explosive bomb struck and penetrated the north cantilever, exploding over the tramway subway.”

Navigating Waterloo Bridge

Eric Carpenter, who has shared his knowledge of the Thames with me in earlier articles, and who worked at Cory Waste Management at Charlton from 1984 until his retirement in 2008, told me that: “Extra care is needed to navigate bridges positioned on bends in the river as is Waterloo Bridge.” Coming upstream, “the tide wants to flow in a straight line, so when it comes to a bend, it ‘sets’ into the bend and consequently takes the tow with it.” However, at Waterloo Bridge “on the flood, the tide sets towards the north shore, so not too much of a problem because the arch is quite wide.”

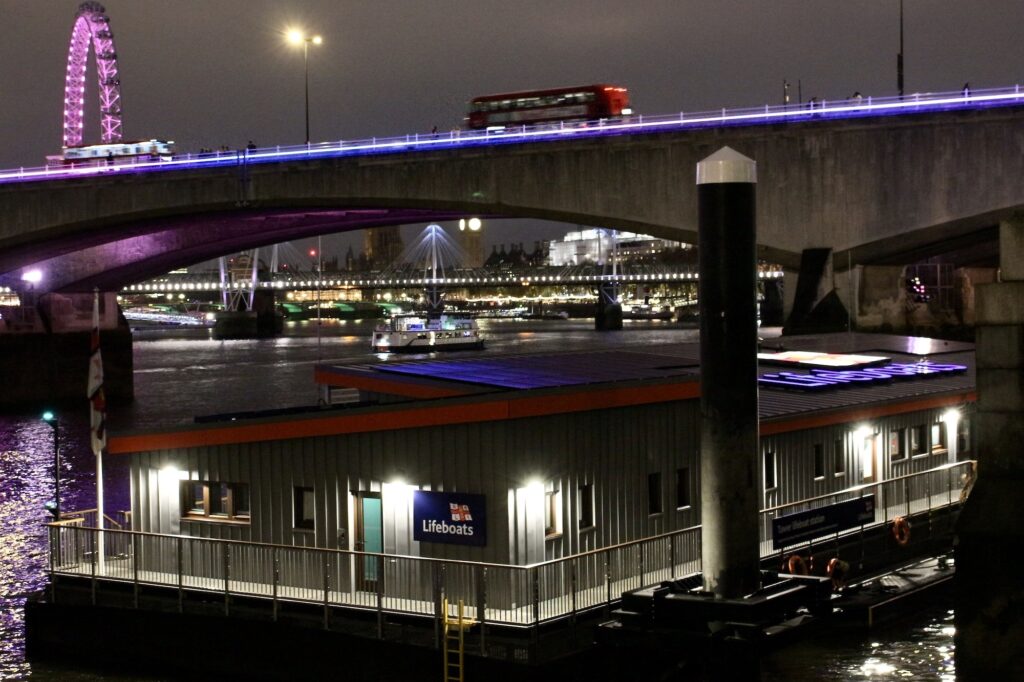

There, on watch throughout every day and every night, all year long, are the permanent crews and volunteers of the Tower RNLI Station. The positioning of their station is of historical significance for it replaced a floating police station whose officers had frequently to deal with deaths, injuries, and those wanting to commit suicide. Rob Jeffries, who served for many years at Waterloo Pier, when its was acting as a river police station, sent me an article of his on H.V. Morton’s book Nights of London from the 1920s. In it a passage called ‘Under Waterloo Bridge’ which Morton recalls a visit which illustrates this point, saying: “I know of few more dramatic places in London than the Suicide Room of this police raft; the bed ready, the bath ready, the cordials ready. The little dinghy with the rubber roller on the stern, its nose pointed to the dark arches.”

London owes much to the twenty-four hour, all-year cover of the Thames Marine Police, now based at Wapping; the four RNLI Stations along the tidal Thames: Teddington, Chiswick, Tower and Gravesend; and the London Fire Brigade fire rescue boats. Their presence on the river has saved many lives.

Journalist and travel writer H.V. Morton, had a great connection with the Thames. At the end of the piece quoted by Rob Jeffries he writes,“I glanced back from the Embankment and saw the Thames heavy with the secrets it has carried to the sea these thousand years…”, and so Waterloo Bridge arches over the unknowable while the tides ebb and flow as always beneath.

Main sources and further Information

Film “The Ladies’ Bridge”, produced by Jo Wiser and Karen Livesey

Channel 5 documentary: Rob Bell’s Bridges that Built London

London County Council programme “Opening of Waterloo Bridge”, Monday 10th December 1945.

London Remembers: Waterloo Bridge

Manchester History: Waterloo Bridge

The History of London ‘The original Waterloo Bridge’

The Ladies’ Bridge: Source material to accompany the film.

Thanks to Wal Daly-Smith, Rob Jeffries and Tom Kinghan, for pointing me in the right direction.