… that I have chosen from among those in: “London: A Pilgrimage”, with text by William Blanchard Jerrold, 1872.

Before working on “London: A pilgrimage” with his long time friend Blanchard Jerrold, – they met in 1855 covering Queen Victoria’s landing in Boulgone – Gustave Doré had become well known in Britain for his striking illustrations of the works of Lord Byron and an English language version of the Bible. After Doré’s exhibition and the opening of his gallery in New Bond Street, (1867-68), Jerrold suggested they collaborate on the creation of a book to bear witness to life and its inequalities in London, with illustrations by Doré and text by himself. Doré agreed and signed a contract with publishers Grant & Co., binding him to stay and work in London for three months a year, for a generous fee of £10,000.

Despite criticism that it showed London in a bad light, their book was a great commercial success. Peter Harrington writes in an article that: “Doré’s characteristic touches of grotesque fantasy appealed to the Victorians’ taste for the Gothic. His popularity was so great that he employed a team of forty wood engravers to complete his commissions.”

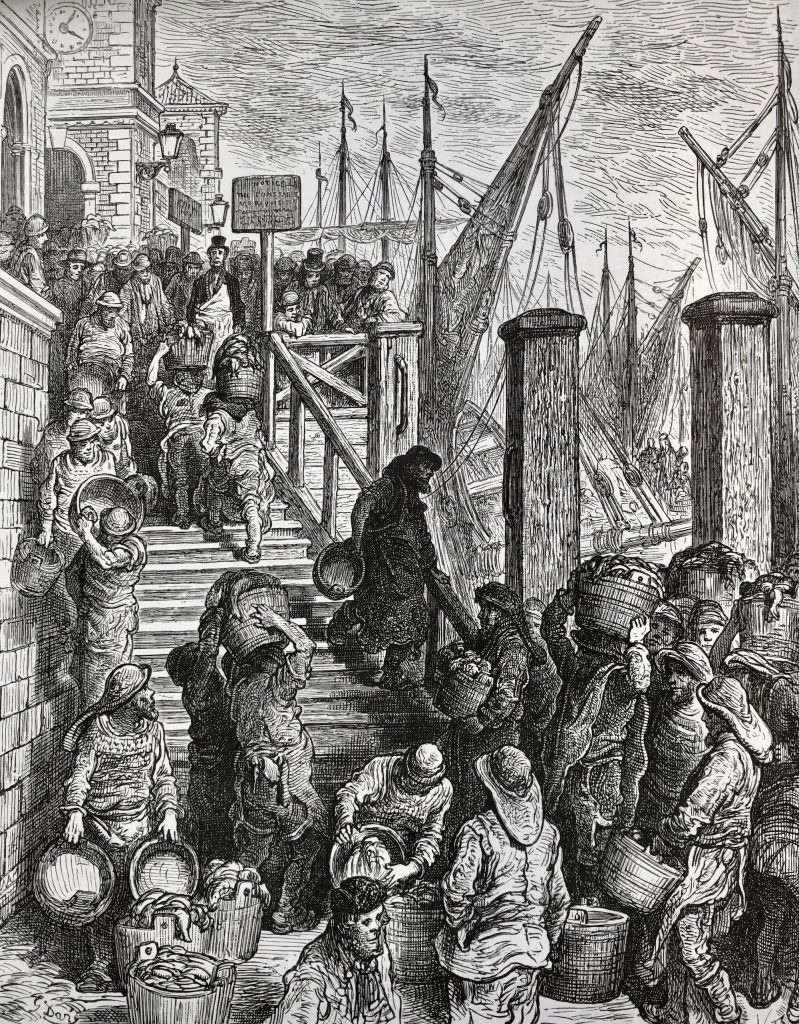

In the Introduction, Jerrold writes that his note books were filled with ideas for studies to be made along the Thames, before entering the streets of London including “smacks, barges, shrimp-boats, the entrance to the Pool, the Thames Police, the ship-building yards, sailors’ homes and public houses, a marine store, and groups of dock labourers…”

Admitting that it would be impossible, within the limits of a book, to do justice to “the greatest city on the face of the globe”, he explains that it will gather together : “the extremes of London life, the valiant work, the glittering wealth, the misery and the charity which assuages it, the amusements and sports of the people, and the diversions of the great and rich.”

There have been conflicting interpretations of this picture. A writer from the Media Store House describes it as “A poignant moment in time, captured beautifully by Gustave Doré’s print of ‘A Waterman’s Family’ from 1872. This powerful image tells a story of love and resilience amidst the bustling streets of London, highlighting the struggles and triumphs of everyday people living on the banks of the River Thames.” And the same writer at the Media Store House, selling the image not only as a framed print but also, curiously but why not, as a jigsaw puzzle, adds: “With each piece, you’ll uncover the story of this charming waterman family, brought to life by Doré’s masterful brushstrokes.”

The Victorians enjoyed discovering stories in pictures and here the family seems to be in some trouble, so I’m not sure that “charming” quite fits the bill, striking though the image is. A young angry, or drunken man, mouth open, arms spread wide perhaps in despair, leans back on a wall at the top of the stairs; and a doleful woman, with far away eyes, is holding onto a child. Next to her stands a young woman, with a defiant look, hand on hip; while down by the waterfront an elderly, bearded man is in conversation with another younger man.

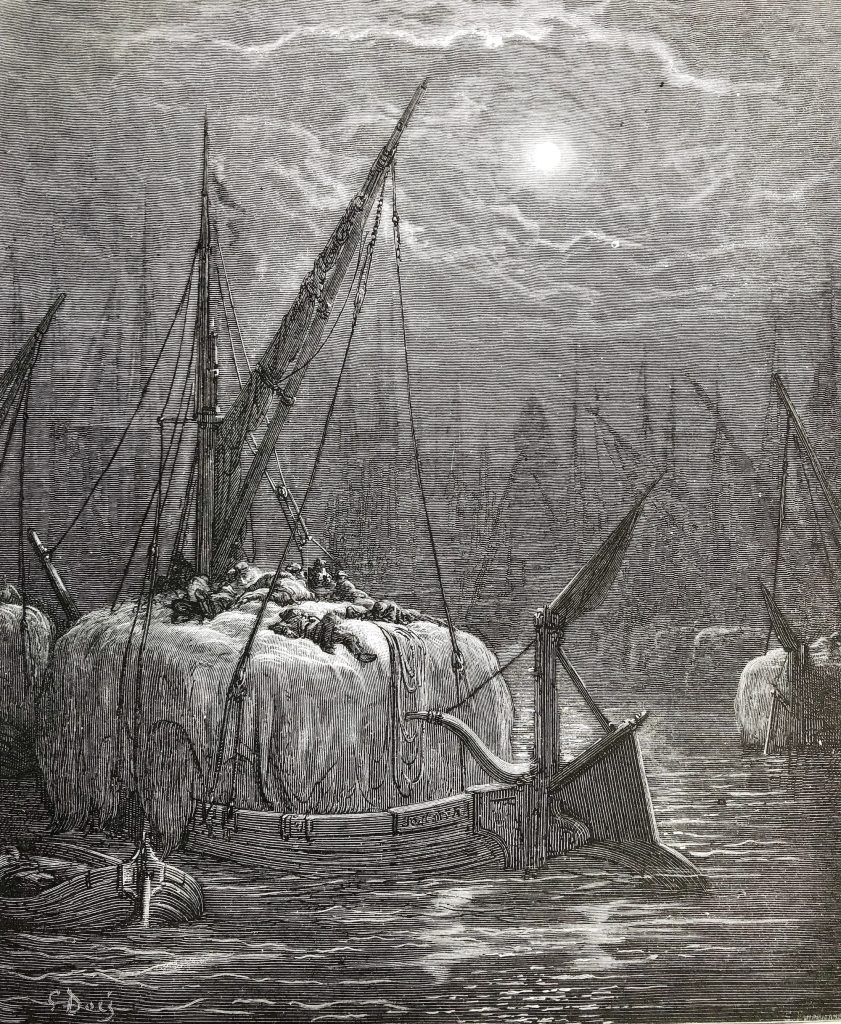

Writing about their passage past Greenwich, Jerrold brings to life the bustle of a busy river ….”Before us the tugs went to and fro in quest of Indiamen or towing clippers that were rich with gold from the Antipodes. The hay and straw barges went gently with the tide, and we talked of a sleep upon the hay, under the moon’s light, along the silent highway.” An image realised in the picture above. He adds to the scene: “The barges of stone and grain went in the wake of the hay and the passenger steamboats cleverly rounded them, now and then with the help of a little bad language.” And he finishes this passage with an interesting reference to mudlarks: “The Greenwich boys were busy in the mud below, learning to be vagabond men, by the help of the thoughtless diners flushed with wine, who were throwing pence to them.”

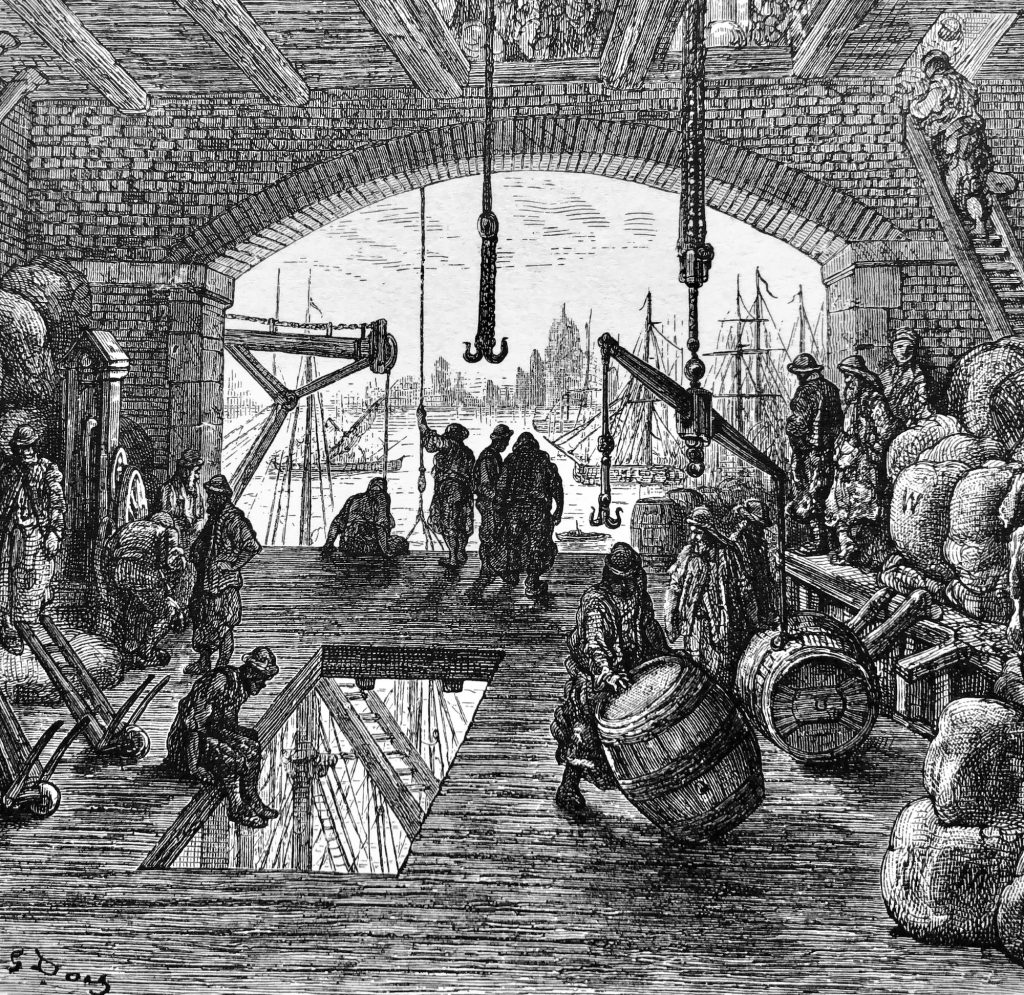

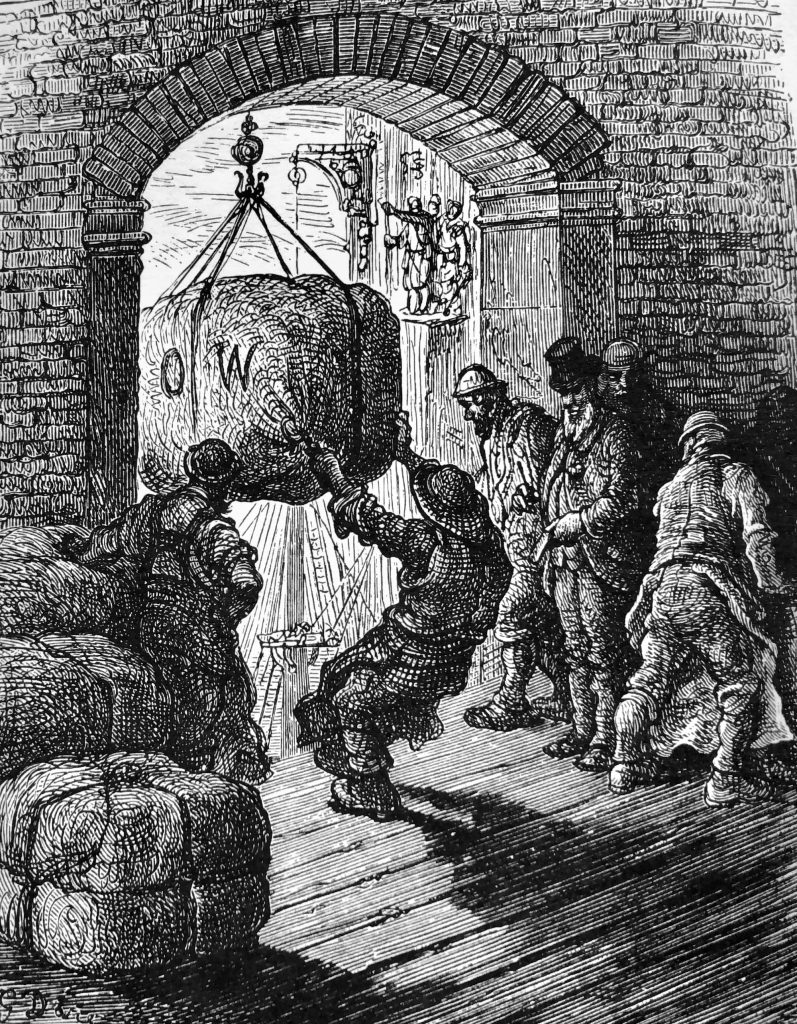

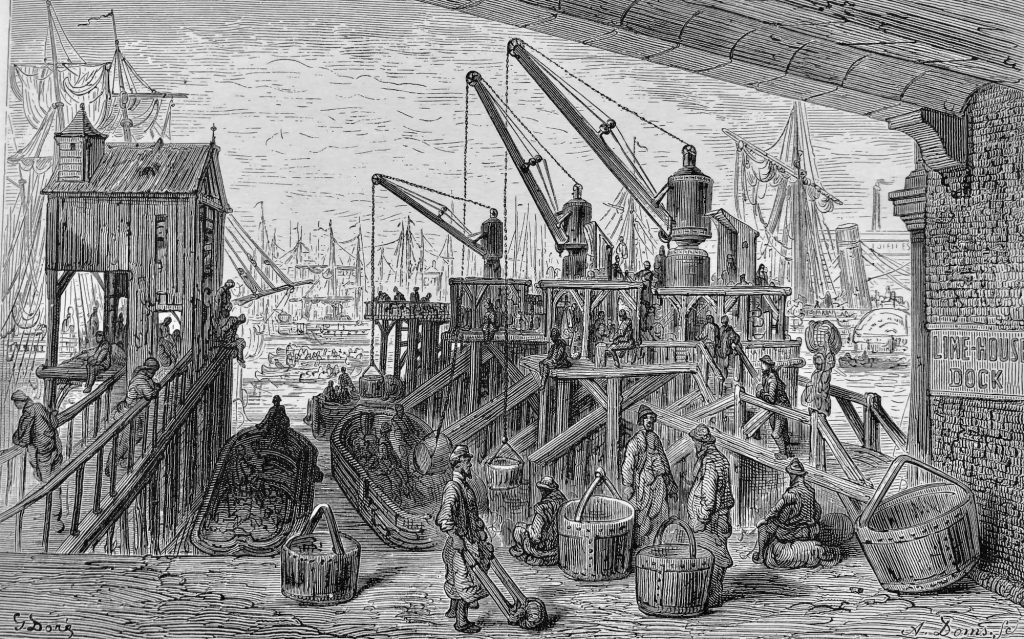

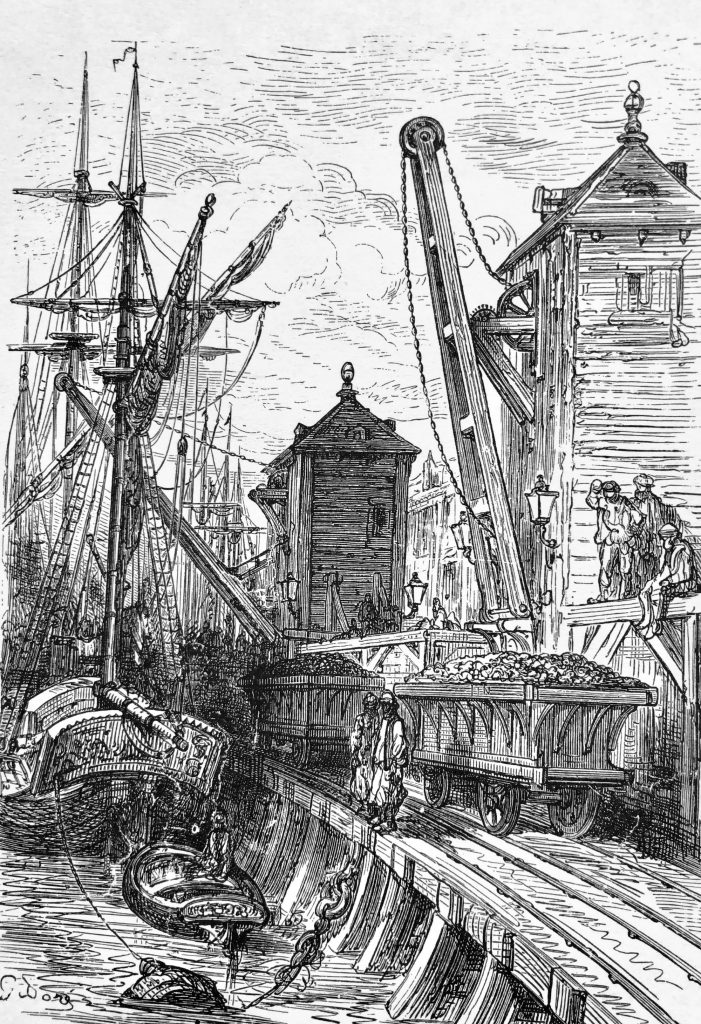

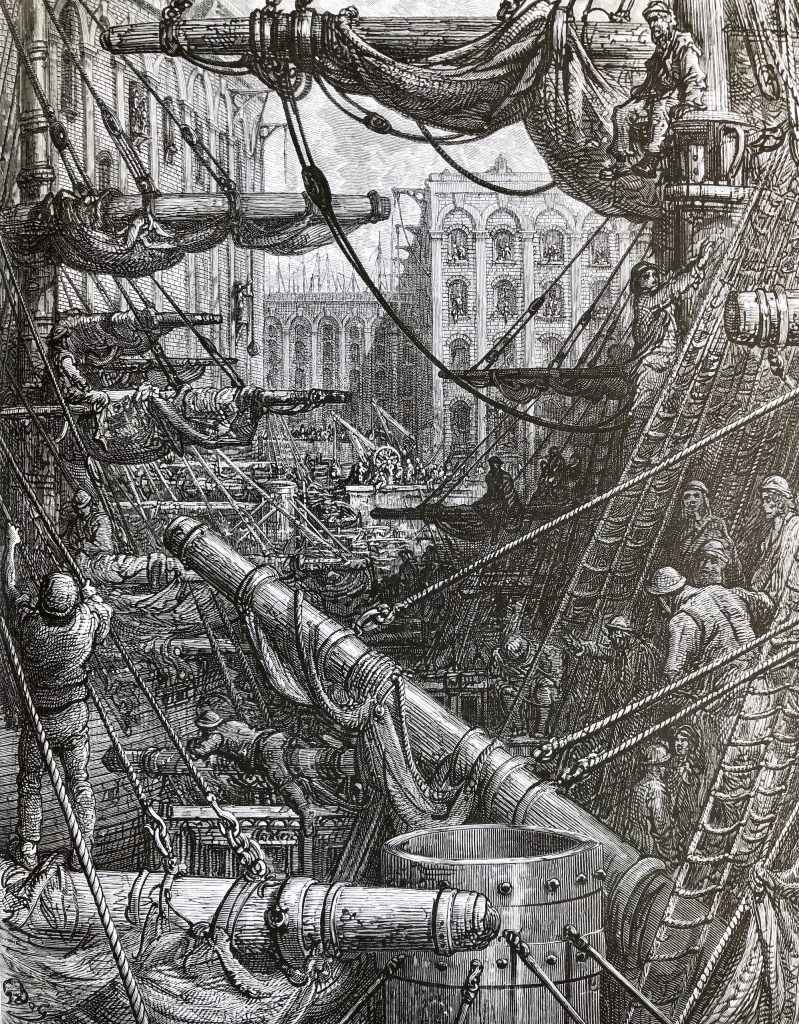

A whole chapter in the book is devoted to the docks in which both Jerrold and Doré bring to life the extraordinary variety of goods that passed through them along with sailors from all nations over the world.

Sitting on some barrels by St. Katharine Dock gates on a “sultry Summer’s day” they observe the scene before them…”lost in the whirl and movement. Bales, baskets, sacks, hogsheads, and wagons stretch, as far as the eye can reach.” There is a cast of “solid carters and porters; dapper clerks, carrying pen and book; Customs men moving slowly; slouching sailors in gaudy holiday clothes; … grimy firemen (shadows in the throng) and hungry-looking day-labourers landing the rich and sweet stores of the South.”

Walking round the busy basins, they found their way – “through bales and bundles and grass-bags, over skins and rags, and antlers, ores and dye-woods, through pungent air, and a tallowy atmosphere — to the quay.”

Doré and Jerrold were particularly taken with the Concordia whose “figure-head was stretching out of the basin and overshadowing the quay. A noble representative vessel in the midst of this mast-forest , and by the banks of the busiest river in the world.”

Describing their approach to London Bridge Doré depicts the bustle and commotion of the crowds while Jerrold conjures up the soundscape: “The creak of cranes and rattle of pulleys ; the pulses of the steamships under way ; the flapping of idle sails, the hoarse shouts of sailor-throats, the church bells from many quarters; and through all, the musical liquid movement and splashing of the water, strike a cheery note in the brain of the traveller who comes to us, by the Port, to London.”

He invites his readers into another world of the senses: “The air is filled with mingled odours of fruit and fish… Oyster-shops, with cavernous depths in which hasty men are eating, as my companion has it, ‘on their thumbs’; roomy, ancient fish warehouses and fruit stores on the north side and only fish everywhere on the south side…”

All the time he notices the backdrop to London life that will be so vividly captured by Doré, “At hand the sky is webbed with rigging… And the forests of masts that stretch far inland, lend to the docks a limitless expanse in the imagination.” Closer at hand he remarks on the “dark lanes and ancient broken tenements; the corner public houses delightfully straggling from the perpendicular; the crazy watermen’s stairs; the massive timber about the old warehouses; the merchandise swinging in the air midway from the lighter to the storage; the shapeless black landing-stages; and the uncouth figures upon them…” And there to keep order as best they can, “The stern faced Thames police pulling vigorously from under our bows.”

****************************

A number of Doré’s Thames engravings combined with Jerrold’s descriptions take us back to a Dickensian world, a world of extreme contrasts between rich and poor that still, though mitigated, echoes today. And yet, when describing and illustrating the Thames at work, they not only show hardship they also show how fundamental the river was to the commercial success of London at the centre of the British Empire. It was a world still rooted in the DNA of long established families of London and the Thames, whose history and many traditions flow inextricably along with those of the river.

Sources and further information

London: A pilgrimage: Doré, Gustave, and Jerrold, Blanchard, London, Grant & Co., 1872.

A London Pilgrimage by Gustave Dore and Blanchard Jerrold, from the Digital Archive of India.

Doré’s London: All 180 Illustrations from London, A Pilgrimage, New York, 2004

Royal Academy: Gustave Doré (1832 – 1883)

The London Museum: Gustave Doré’s London Pilgrimage

Peter Harrington, ‘The Journal’: Doré’s London

Media Storehouse ‘A Waterman’s family’

If you are interested to see other aspects of Doré’s work see: Gustave Doré’s East End by The Gentle Author