Waterman and Lighterman of the River Thames

Working for fifty years on and around the Thames, Eric Carpenter has a map of the river, its tributaries and canals indelibly etched into his brain. I’m lucky to meet him in St. Katharine Docks a couple of weeks before *lockdown* as not only has he told me something of his life on, and love for, the river Thames, he has kindly helped me with my recent articles on the 1907 book The Thames from Chelsea to the Nore.

He has a jumper with a distinctive badge: the coat of arms of the Company of Watermen and Lightermen and explains, “Only Freemen of the Company are allowed to wear their badge, so I had to prove that I was a Freeman before being allowed to buy it.”

Eric went through a rigorous seven-year period of training on the Thames to become a Freeman of the Company. He was apprenticed at Waterman’s Hall in August, 1958. He was just fifteen years old. His father, William Carpenter, an experienced Waterman and Lighterman was his “Master” and as such it was his responsibility to help his son find employment and to make sure that he learnt his trade. Eric’s first job was on the tug SIR JOHN, owned by Humphrey and Grey Lighterage Co. He worked under Captain Jess Handley. “I started my career as ‘the boy of the boat’ or the dogsbody. My duties were keeping the cabins clean, washing up after other members of the crew, polishing the brass lamps and helping the mate on deck.”

The SIR JOHN was based at Battlebridge Roads, roughly where H.M.S. BELFAST is now moored, and among the myriad sounds and smells, Eric can particularly remember “the strong smell of smoked bacon coming from the Danish ships in the Upper Pool.”

There were so many new experiences and so much that he had to learn that it’s impossible to do justice to them here. However, Eric tells me two things that illustrate the practical experience and depth of knowledge of the Thames required to gain his licence. Firstly, part of his “time at H & G was spent in the Rope store”, an area at Hay’s wharf where ropes were cut at various lengths for use on the craft. Apprentices were taught how to splice ropes, some nine inches in circumference, also, to splice wire hawsers which were a bit more tricky!”

Secondly, he tells me about ‘driving’ or rowing a boat under oars – adding that another name for an oar is a ‘sweep’. “It was not obligatory for an apprentice to undertake a ‘drive’ but it was looked upon favourably by the examining court at the time of your two year licence appearance.” It was also a good way to learn to understand the river and its characteristics.

“Undertaking a ‘drive’ taught you so much regarding tide sets, where the tide ran fastest, where the ‘slack’ tide was, and how to take account of the wind factor.” This was important because “the wind would have a greater affect on an empty barge than a loaded one. Also, it taught you how to look ahead to plan where to position the barge. Rowing a barge or being in control of a vessel is like a game of chess, you have to plan ahead to position the vessel before you actually get to any situation, whether it’s passing through a bridge or rounding head onto the tide.”

‘Calling a drive’ means talking through the complexities and details of a particular drive to the examining committee, a bit like ‘The Knowledge’, the rigorous exam taken by London black cab taxi drivers. “It was handy to have several drives under your belt.”

In 1959 on the advice of his father, he moved to work for General Lighterage as they took all kinds of cargo the length and breadth of the river Thames and its tributaries. He gives an idea of the enormous variety and scope of their work: “We took grain and general cargo to Dartford Creek; timber, and would you believe it barges full of asbestos, to Barking Creek; copper bars for onward travel to Brimsdown rolling mills; bags of coffee to be taken up to Ware in Hertfordshire; zinc to the Hackney Lesney factory, makers of Matchbox toys; plywood; timber and coal all to Bow Creek adjoining the river Lea.” Some of the cargo passed through Thames lock to access the Grand Union Canal, including “bags of beans for the Heinz factory at Uxbridge, and I remember barges with slabs of marble being pulled up the canal by tractors”. He adds, “With regard to the river Lea, at 6 a.m. from Monday to Saturday at Bromley locks you would have five or six dock tugs towing four to six barges each, setting off for various wharves along the river.” Dock tugs were small tugs that could work within the docks or along the canals. Tugs often have quite punchy names. He remembered: Express, Energetic, Jamar, Valcary and Ensign.

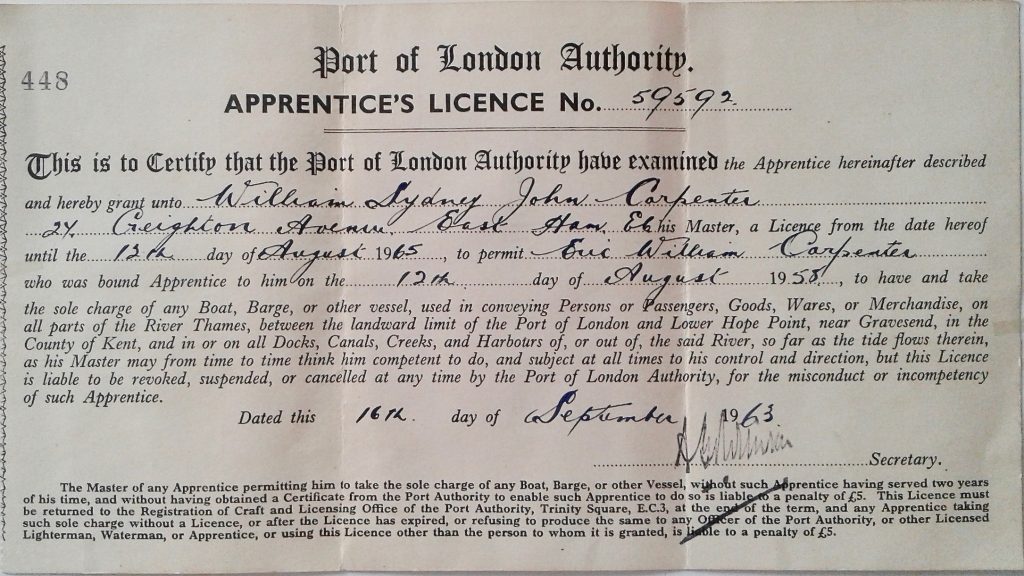

“After two years afloat I went back to Waterman’s Hall to be questioned on my knowledge of the river, in order to gain my two years’ licence”. He was faced with questions by the Court, a wall of examiners sitting round a horseshoe table. A daunting experience but he passed. This meant that he was licenced to “have and take sole charge of any Boat, Barge, or any other vessel, used in conveying Persons or Passengers, Goods, Wares or Merchandise on all parts of the River Thames, between the landward limit of the Port of London and Lower Hope Point, near Gravesend…” However, he still would be under the control of his Master at all times, who would judge in every case whether he was competent to take on a particular task. And there was a warning that the licence would be “liable to be revoked, suspended or cancelled at any time for misconduct or incompetency”. Happily this was not a problem for Eric and at the end of his apprenticeship five years later he had to appear before the Court once more with evidence of his experience afloat and to answer questions on navigation. After passing this final test, he became a Freeman of The Company of Watermen and Lightermen.

He remembers “feeling like Superman after gaining his licence. “You could now take barges anywhere, tow to Brentford, undock out of Limehouse cut…” and he recalls, aged eighteen, “towing up to Nine Elms cold store in the middle of the night, with a barge full of cartons of butter, climbing over the locked-up wharf gates, walking over Vauxhall Bridge to Victoria to catch the night bus home. He adds that he liked his work. “I really enjoyed being out on the barges, there was more freedom in the open air.”

Eric’s career continued in much this way for his company, which had since become the Thames and General lighterage Co., until 1971, when with the advent of containerisation and changes in transportation and working practices, he transferred to Tilbury Dock where he worked for twelve years supervising the loading of the company’s barges. Work was tough and he has a wealth of stories to tell. On one occasion, “In 1975 Thames and General won a contract to transport refuse from London Wharves to a landfill site up Holehaven Creek, near Canvey island, Essex. I can remember waiting at Egypt bay on the Kent side of the river for the tide to rise on a pitch black winter’s night, and wallowing across the river, the tugs decks under water, the six barges bouncing up and down and having to watch out for inbound ships.”

Eric’s final job was with Cory Waste Management now Cory Riverside Energy, whose tugs with their barges of bright yellow containers you will probably have seen if you have ever been on a Thameside walk in central London, and you can follow his story on this site in Part 2, The Cory Years... from May 31st.