Beginning where I left off in the last article, with some of the varied works of art to be found along the central London Thames, here is another view of Thomas Thornycroft’s heroic statue of Boudicca on the west side of the river. In full charging mode she appears to be heading south towards the Palace of Westminster…

Often passed with rarely an upward glance by the thousands thronging across Westminster Bridge, the South Bank Lion looks wistfully to the east. Sculpted by William F. Woodington in Coade stone, and originally painted red, he first stood at the top of the Lion Brewery facing theThames in 1837 and remained there, surviving among widespread bomb damage to the surrounding area during the Second World War. Saved by a London-wide petition strongly aided by the advocacy of King George VI when the brewery was demolished, it was installed outside Waterloo Station, one of the entrances to the Festival of Britain in 1951. The Lion was finally, restored in 1966 and placed close to Westminster Bridge where it now stands. See: London’s Favourite Lion.

The golden eagle presiding over the Royal Air Force Memorial and shining proudly across the Thames, was designed by William Reid Dick and stands on the top of the monument designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield. Completed in 1923, it was dedicated to the airmen who died in the First World War. “In 1946 additional inscriptions were added in memory of those who lost their lives in the Second World War. On September 15 every year the Chief of the Air Staff places a wreath at the foot of the Memorial to commemorate Battle of Britain Day, and every Remembrance Day the Fund lays a wreath.” From the Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund.

Ellen Castelow writes that “Britain wanted something big and noticeable to commemorate the British victory over Napoleon sixty-three years earlier.” After a hazardous journey from Alexandria, which nearly saw the 3,500 year old artefact sink into the sea, Cleopatra’s needle arrived to cheering London crowds in January 1878.

Across the river from Cleopatra’s Needle is one of my favourite sections of the South Bank: the stretch of embankment between the London Eye and the Hungerford Railway Bridges. For it is here that hundreds of *living statues* have over the years, delighted crowds with their imaginative costumes and their ability to stand absolutely motionless until a coin is dropped into a hat, or bowl beneath their feet. And then you might have a smile, a nod of the head, or a gentle wave.

Close by the living sculptures is an abstract sculpture, un-noticed by the majority of South Bank crowds: ‘The Jubilee Oracle’ cast in bronze resting on black marble. Sculptor Alexander whose works can be found in art museums around the world, writes that his work was “influenced by Henry Moore, who later became a good friend, and Barbara Hepworth, who I never met.” The inscription on the black marble below explains his philosophy: “Mankind is capable of an awareness that is outside the range of everyday life. My monumental sculptures are created to communicate with that awareness in a way similar to classical music. Just as most symphonies are not intended to be descriptive so these works do not represent figures or objects.” And this sculpture evokes that awareness.

A celebratory monument dedicated to Samuel Plimsoll, stands on the opposite side of the river on Victoria Embankment. As a member of parliament, his campaign against the overloading of cargo ships eventually led to the Merchant Shipping Act of 1876, which made law the use of loading marks on the side of ships. Known as the Plimsoll Line “They consisted of a circle with a line through it at the level the water would reach when the ship was fully loaded.” Despite fierce opposition from *interested* parties, his determination to see the Act through Parliament won the day and thereby thousands of seafarers’ lives were saved. The inscription on the monument reads: “Erected by the members of the National Union of Seamen, in grateful recognition of his services to the men of the sea of all nations.”

The stone head of Father Thames looks out somewhat mournfully from an arch along King’s Reach.

Art is in a constant state of flux beneath the Southbank Centre as bright graffiti murals come and go in a flash, leaping across your sightline as do the gutsy, gravity defying skateboarders and bikers darting about the Undercroft

To the delight of children, and many grown-ups, there are often street performers blowing bubbles along the riverside. Every prolonged breath creating a new picture.

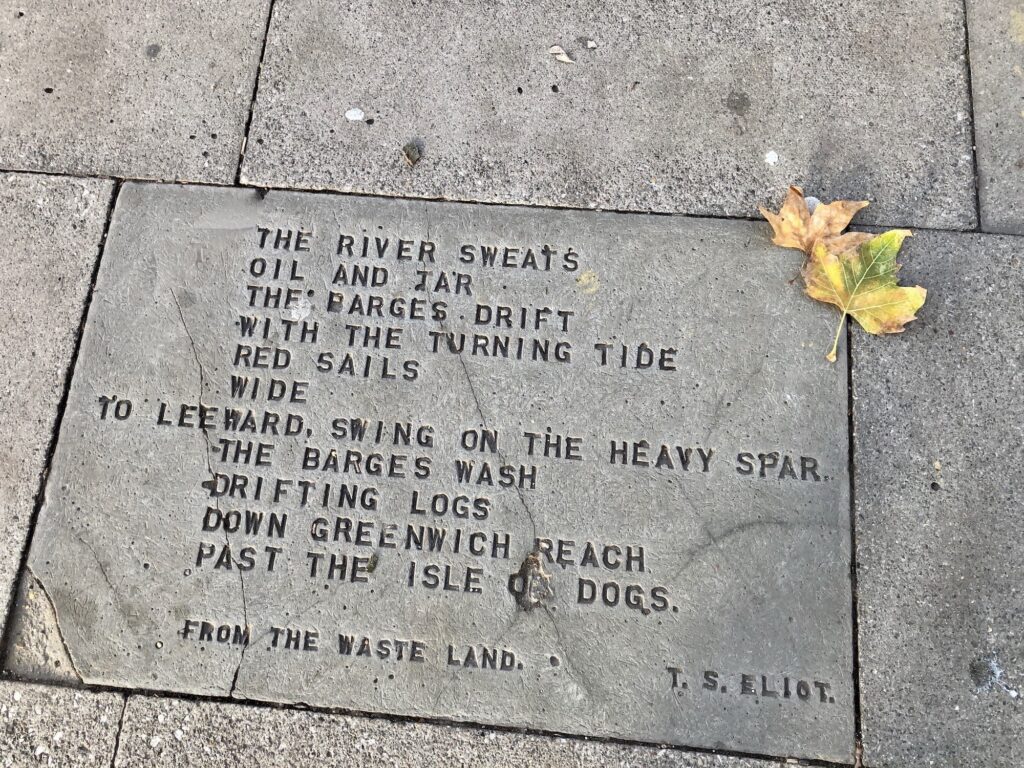

Etched into the pavements, not far from the National Theatre and Southbank Centre, you can see verses written about the Thames by famous poets. They are all damaged now, even this, my favourite, one of the many references to the Thames, from The Waste Land by T.S. Eliot.

Here standing on Waterloo Bridge, is just one of Antony Gormley’s statues cast from his own body form, and part of a large-scale sculptural project called Event Horizon which appeared in 2007. Thirty-one statues were placed on buildings close to the Thames, the idea being to encourage the looking up above street level, however there was some concern that the sculptures were real people contemplating suicide.

Sculptor Angela Conner’s statue of Laurence Olivier, one of Britain’s most famous actors, in a dramatic pose, stands on a plinth in Theatre Square facing the entrance to the theatre that bears his name and with whose creation he was closely involved.

Originally created in plaster for the Festival of Britain in 1951, the sculpture ‘London Pride’ by Frank Dobson was recast in bronze in 1987 and set outside the National Theatre on the South Bank. It started out as part of an artistic programme for the Festival of Britain featuring over thirty sculptures by leading British artists of the day.

Ephemeral art dictated by the rhythm of the tides, is one of the pleasures to discover along the shore of Gabriel’s Wharf. Sand sculptures, some in great detail, others such as a sofa on which the artist sits until completely surrounded by water, have more of a traditional sandcastle feel.

As you walk along the Thames Path, heading downstream passing beneath the Blackfriars Bridges, you will come across the splendid London, Chatham and Dover railway coat of arms with the shields of London, Kent, Rochester and Dover dated 1864. A real statement of pride in the age of steam trains.

Further downstream you will come across another statement of pride, one of the City of London’s boundary dragons set on the east side of London Bridge. Ian Mansfield writes that the design is “based on two huge dragons that once stood above the entrance to the Coal Exchange.” An impressive building opened in 1849 it was demolished in 1962, an act of vandalism described by Lost Architecture as “one of the great conservationist horror stories.”

Seen from across the river, or fleetingly as you pass by on a boat, The Monument commemorates the Great Fire of London in 1666, which destroyed or severely damaged many thousands of houses and businesses. It was designed by Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke.

Just a few of the painted elephants in London’s 2010 ‘Elephant Parade’ that brightened the riverside and parts of the city. There were 250 elephants standing or sitting, each designed and decorated by a different artist. In June 2010, an auction of the elephants raised four million pounds which went to secure a vital area of elephant habitat in Kerala, India.

Unveiled in June 2012, a month before the opening of the Olympic Games in London, the distinctive Olympic rings, conceived by Pierre de Coubertin in 1913, gave an extra dimension to London’s most famous landmark. Looking back, it seems that the pride and togetherness felt by so many across the country then has for the moment been lost…

To be continued…

Sources and Further information

See article by Ian Visits ‘A History of the South Bank Lion’.

The Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund, RAF Memorial.

Article by Ellen Castelow: Cleopatra’s Needle

See article London Details on Plimsoll and his monument by Baldwin Hamey, also the Science Photo Library.

Sculptor of London Pride Frank Dobson.

History of The Monument.

For the story behind the City of London dragons, read Ian Visits

The London Elephant Parade, 2010.