The final stage of our journey downriver with artist T.R. Way

This first picture on our continuing journey downstream is of Gravesend seen from Rosherville Pier. Thames Waterman and Lighterman, Eric Carpenter, who has kindly been sharing his extensive knowledge of the river as we travel along Thames Past, explains that this is a view towards the Royal Terrace Pier, though this is not shown in the image. He adds: “Terrace Pier is the heart of riverside Gravesend, it serves as the hub for ships’ Pilots, Watermen and tug crews.”

It is now also the headquarters of the Port of London Authority’s Pilotage Service. A passage on their website explains what they do: “Fourteen specialist River Pilots work in the stretch of the Thames between Gravesend and London Bridge. Four of these are Bridge Pilots working upstream from London Bridge to Putney Bridge, where expertise on the shallower water and low air draughts is vital, particularly for awkward one-off project type cargoes.”

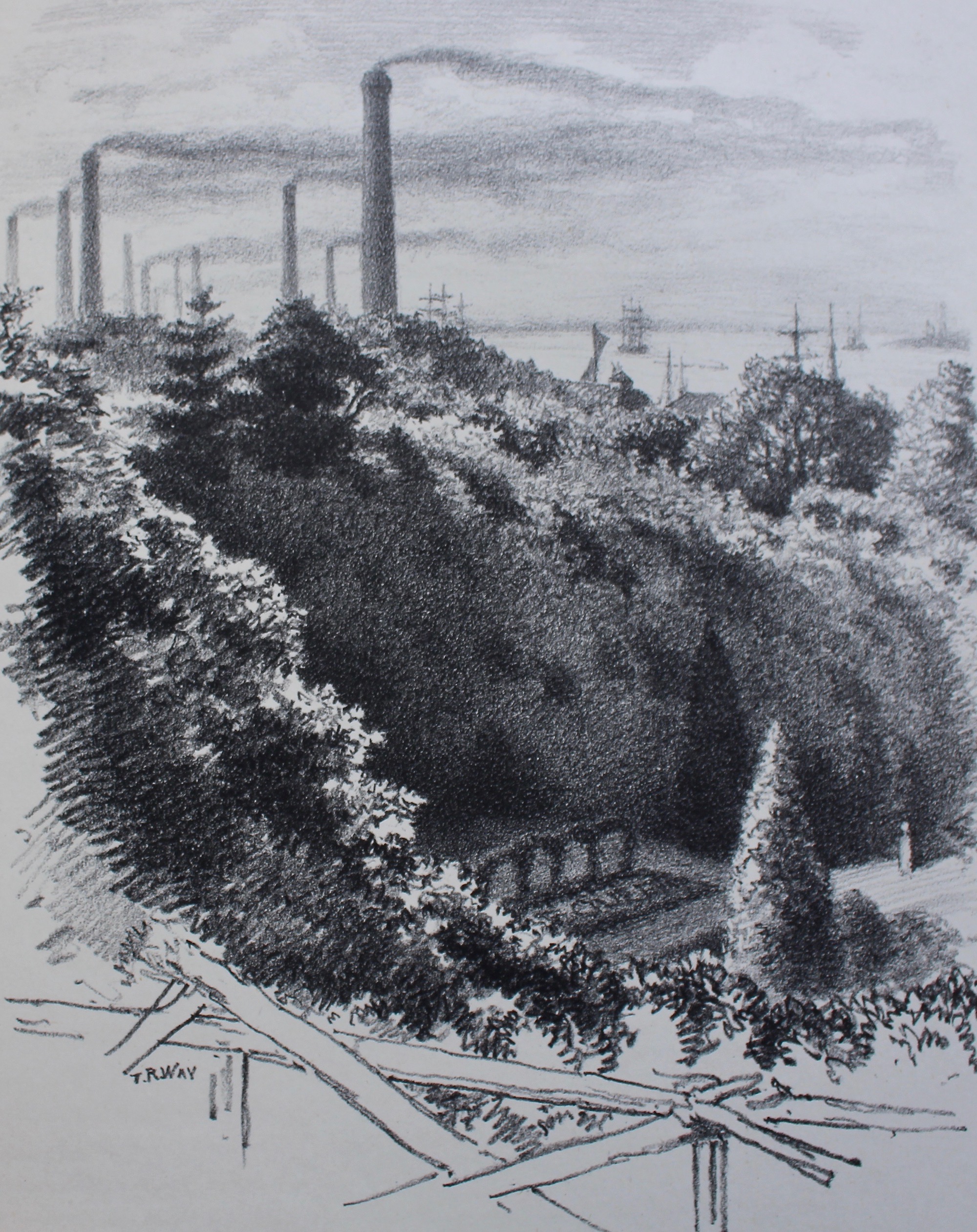

Rosherville Gardens was a very popular pleasure garden in Victorian times. In her book The Place to Spend a Happy Day: A history of Rosherville Gardens, Lynda Smith describes the many boats crowded with day-trippers from London landing at the nearby Rosherville Pier. From there they could walk to enjoy a whole host of attractions including a maze, an archery ground and a bear pit set in lovely gardens. Later, restaurants, theatres and an open air stage were added together with a whole variety of popular entertainment such as “fireworks, tightrope walkers, balloon ascents and a gypsy fortuneteller.” It was sailing from there on September 3, 1878 that passenger steamer SS Princess Alice, was involved in a fatal collision with the collier Bywell Castle, in one of the worst British inland waterway accidents ever recorded, with the loss of 640 lives, 240 of them children. From then on, marked by the tragedy, and a public drawn to the new fashion for train trips to seaside resorts, the central London attractions of Hyde Park, and the new museums in Kensington, the gardens fell slowly into decline. In 1899 T.R. Way, heard that Rosherville Gardens were to be sold, and having seen a poster advertising a fête in this once famous setting, he was curious to see them. He boarded The Mermaid at Charing Cross Pier with his family and writes “that it was this trip which at last determined me to go on with a scheme which some years before had been started when making a series of Thames lithographs.” And so began his work with W.G Bell for their book The Thames from Chelsea to the Nore published in 1907.

Tilbury evoked many memories for Eric Carpenter when I showed him the picture of Tilbury Fort, albeit more than half a century later. In 1971 he was transferred from his work in London to Tilbury Docks, where his “main function was the overseeing of cargo discharging from various ships into the barges of the Thames & General Literage Co. The cargo would range from copper bars, sacks of coffee, logs, timber and chests of tea to name but a few…” This was a time before containerisation, when men generally worked closely with identifiable cargoes…

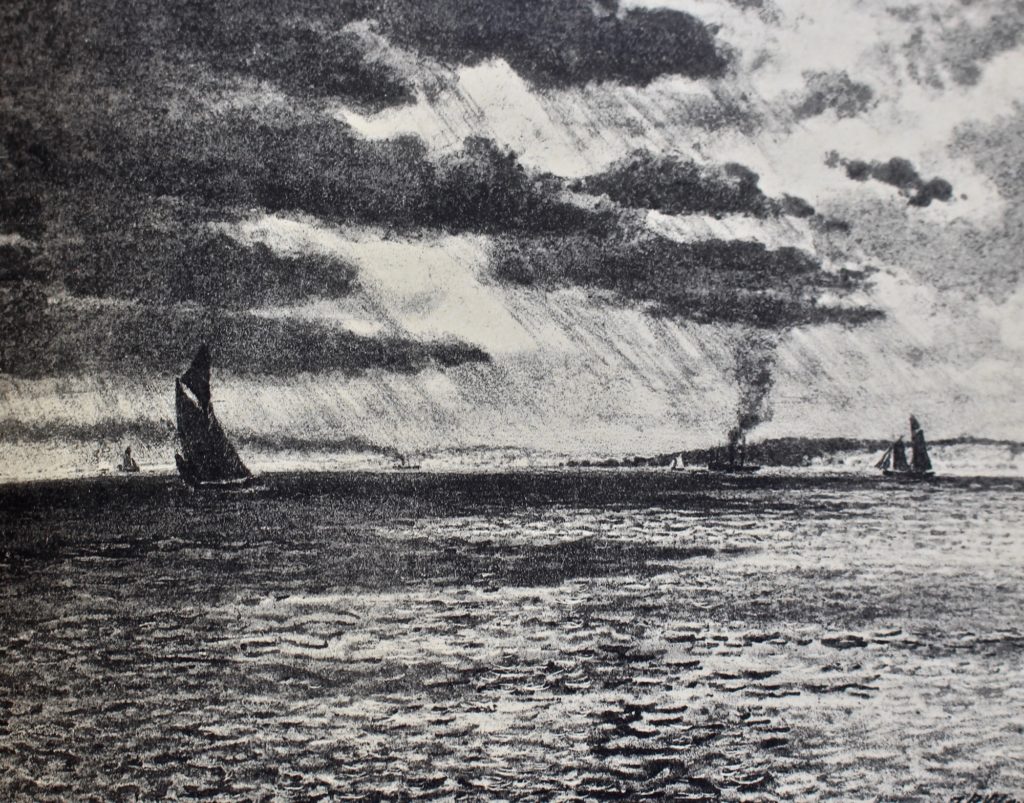

W.G. Bell, author of the text of The Thames from Chelsea to the Nore, has a particular feeling for the spirit of Thames Estuary and its sheer sense of space in contrast to the river’s managed confinement inland, which I’ve heard echoed in other works on the subject. He writes: “The ships passing out to sea or coming up against the tide no longer cluster together but seem to shun each other. They keep a distance apart….The vessel upon which one is travelling becomes a little self-centred world of its own, a point of outlook into the larger universe around.” And observing the mercantile fleets of England he remarks that the open seas “have no such sight as this…The big ocean liner is here a living thing, imposing, magnificent…”, moving with speed but in “the narrower waters upstream it will slow down, become subdued, lose its freedom in the press of shipping through which it must thread a way.” He describes the many hurrying steamers, at variance with “sailing-ships seemingly immovable, contented to pass the day so far as the tide and lightest of breezes will take them.”

Bell ends his description of shipping in the Estuary by writing of the Nore Lightship which marked the treacherous Nore sandbank, the limit of his journey along the Thames with Way: “Least of all in appearance”, compared to all the shipping in the Estuary “but first in importance, for its masthead beacon lights the way for every vessel that sails in and out of the Thames”.

These days the complex navigational safety in operation along the river is managed by the Port of London Authority, here outlined as a basis for yachting or leisure traffic in an interesting short film: Safely navigating in the lower tidal Thames. And in the difficult days of Covid-19 and the lockdown, the Port of London is there for London and the South East, remaining operational, “with over 1,300 commercial shipping movements, keeping essential supplies on the move.” Thank you to them and to all those performing vital services along the river…