Helm at Tower RNLI Lifeboat Station and Casualty Care Trainer for the Thames

The tide was flowing fast upstream as I made my way down a ramp to the Tower RNLI Station on Victoria Embankment to meet Chris Walker. Kindly welcoming me during a break in his shift he led me to a table in the crew’s kitchen where the duty crew can cook something to eat and socialise but still be ready to launch within ninety seconds of a call.

Chris engages with social media, giving a particular insight into the work of Tower RNLI and his part in it, often signing off a tweet with a virtual #TimeForACuppa. But this time he begins with a real one for us both. We feel the movement of the river with an occasional surge, sway or knocking sound caused by the wash of a passing boat as the station is built on a floating pier.

He tells me about the RNLI’s relationship with the river, explaining: “We have to pass a Local Knowledge Endorsement, an intricate test run by the Port of London Authority for all commercial river users. You get a real grilling but it’s vital to know the river intimately by studying the behaviour of the tides in open water, beneath the bridges, round the cofferdams and piers. Cofferdams are particularly challenging because the flow around them changes all the time.”

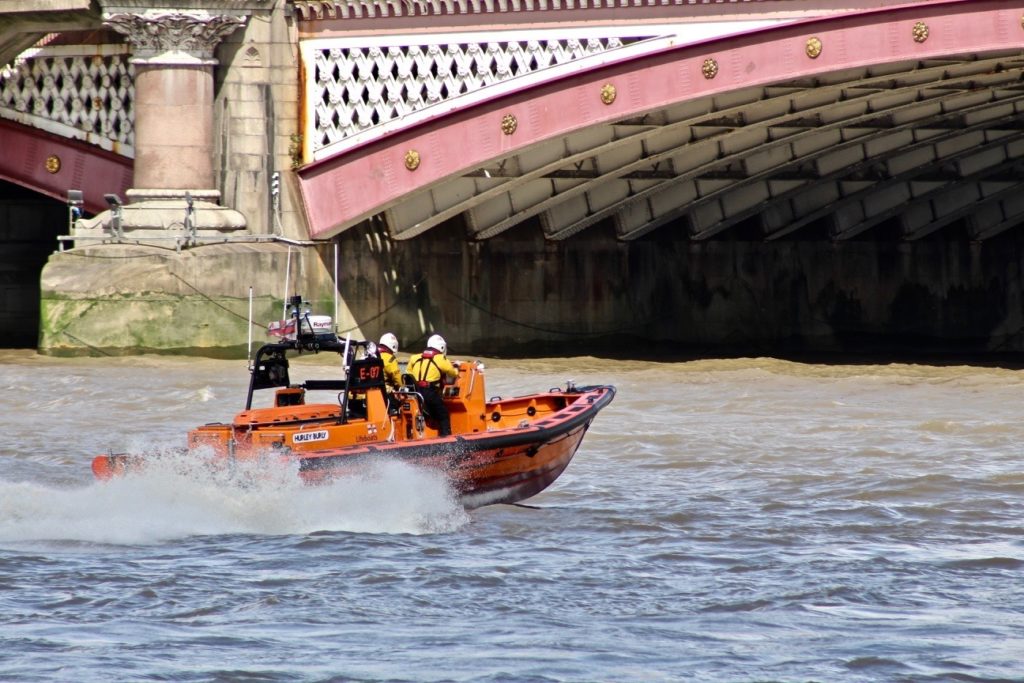

The crews learn to be wary of difficulties such as the turbulent water “bottlenecking” at the Blackfriars Bridges and a standing wave that appears on an ebbing tide caused by a shoal at London Bridge. Speed limits and the often shifting position of beaches and sandbanks have to be thoroughly learnt. And, as if to underline the point, Chris produces a comprehensive, six page, hand drawn revision map marking all the bridges, piers, Thames Tideway construction sites, moorings, boating bases, fuel barges and points of interest. Familiarity with these means that crews can react more swiftly and safely in an emergency.

Considering how long the Thames has been a place of danger, it is only recently that the RNLI set up stations along the tidal Thames. Before that, rescues were carried out by Police vessels. However, following reports into the tragic sinking of party boat the MARCHIONESS on August 28, 1989, when fifty-one people were drowned after the dredger BOWBELLE rammed and sank her near Southwark Bridge, it was decided that the RNLI should have a twenty-four hour presence on the Thames. In 2002 stations were set up at Teddington, Chiswick, Tower Pier and Gravesend; Teddington operating with volunteers summoned when needed as on coastal stations but Chiswick, Tower and Gravesend permanently manned by paid crew working on an organised shift basis. They are joined on station by a team of volunteer crew members, who stay there for the entire shift rather than responding to pagers. Tower has around sixty volunteers on its books and most volunteer for about two twelve hour shifts every month. This means that crews can plan their family lives and come in to work from outside London. In 2006 the Tower Pier station, retaining the name Tower, moved to where it is now by Waterloo Bridge.

Chris explains that the RNLI crews were newcomers to a river community, many of whose families have been working on the Thames for over three hundred years. “As our members passed the tough Port of London tests, and so were put on equal terms with the commercial skippers, we were gradually accepted and respected by the long term river users.” And now they’re very much part of the river community involved with exercises alongside some of the many operators, including joint exercises with Cory tugs, practising the rescue of casualties from awkward places below deck.

Their rescue work covers a whole variety of incidents from people trapped on beaches by rising tides; passengers taken ill on cruise boats; industrial accidents on construction sites; pleasure boats in difficulties; saving people who have fallen into the river by accident, and sadly the recovery of those who, by design or by bad luck, haven’t made it. But like all those working in our Emergency Services and Armed Forces, they support each other through the darker moments.

But there are lighter moments too and time for camaraderie and joking between the Thames stations. “Chiswick is known as ‘the shallow end’; Tower as ‘shiny pier’; and Gravesend as the ‘deep end’. Yet in a crisis they immediately pull together with absolute professionalism. And their sympathy with all sea rescuers extends beyond our borders. On June 13, the duty crew stood silently in memory of three French SNSM (Sauveteurs en Mer) lifeboat crew members, drowned after their boat capsized during a rescue off the Breton coast near Les Sables d’Olonne.

Apart from his position as Helm, Chris Walker is also the Casualty Care Trainer for the Thames and holds regular RNLI training courses at the station. On Thursday, June 18, the session included: the use of immobilisation tools and stretchers, airway management, and the strapping of different kinds of fractures. Other training can include the use of three heavy practice crew dummies, all called ‘Bob’. Usually hanging dejectedly at the end of the station platform, they are placed in a variety of scenarios where crew members have to work out how best to effect and cary out a rescue.

HURLEY BURLY, the station lifeboat, was out with a crew on a training exercise during my visit, though as they were in constant radio contact, they would have been able to respond immediately in the case of an emergency. A class E Lifeboat, she was specifically designed for easy manoeuvrability; to cope with submerged detritus; and to weave between heavy traffic at speed. When Chris is on shift, he is at the helm and he knows her well.

Over his time on the Thames, Chris has become very much attuned to the moods of the river. “There is a palpable pulse, you can feel the pulse of the river and, under certain conditions you expect something to happen.” And he clearly loves working there. Though his work does have its difficult and sometimes tragic side, this is offset by the breathtaking beauty of the river both by day and at night. Seeing London’s buildings and bridges from water level “You get to discover things that no one else knows.”

Chris Walker, drawn to the sea and familiar with boats since childhood, has been involved with the RNLI since his first days of volunteering for the Helensburgh Lifeboat in Scotland. He came south to do his degree and still committed to saving lives at sea, volunteered for the Calshot Lifeboat in Southampton Water. He became a lifeboat trainer at the RNLI College in Poole and after a spell at Chiswick, further upstream on the Thames, came to take on the role of Helm at Tower. As well as his training and instructing role, he is also part of the RNLI Flood Rescue Team and an RNLI Instructor. In September 2018 he was delighted and proud to receive a Long Service Medal.

On the alert for twenty-four hours every day of the year, London is lucky to have dedicated and experienced RNLI teams covering the tidal Thames. And Tower is its busiest station. Their ‘scores on the door’, since the station opened in 2002, accurate at the time of writing, show that they have had 7,760 call outs, or ‘shouts’ with 311 lives saved, meaning that their intervention has actually made the difference between life and death for the casualty. But the lives they have saved are not just human, a yellow sticky at the foot of their tally board records the rescue of a dog and a Harris hawk in difficulties earlier this year, both restored to their grateful owners.

Thank you to Chris Walker and all the RNLI crews who watch over the tidal Thames.

To learn more visit Tower Lifeboat Station and follow @RescueShrek and @TowerRNLI on Twitter