The punchy names of Venetian tugs set me thinking…

Revisiting an anniversary trip to Venice in 1986 while sorting out photos during lockdown, I came across these tugs captured on film by my husband. Their assertive names made me think of some of the tugs that I’ve come across and photographed on the central London tidal Thames, the most noticeable being the Cory Riverside Energy tugs on their daily trips collecting and removing containers of London’s waste.

Their names ‘Reclaim’, ‘Recovery’, ‘Redoubt’, ‘Regain’ and ‘Resource’ make their mission and determination clear. Working with the tides, barges of empty containers are towed on the flood tide to collection points upstream and the filled containers are taken back downstream on the ebb tide. Punching through the water these purposeful red-capped tugs and their bright yellow containers command attention.

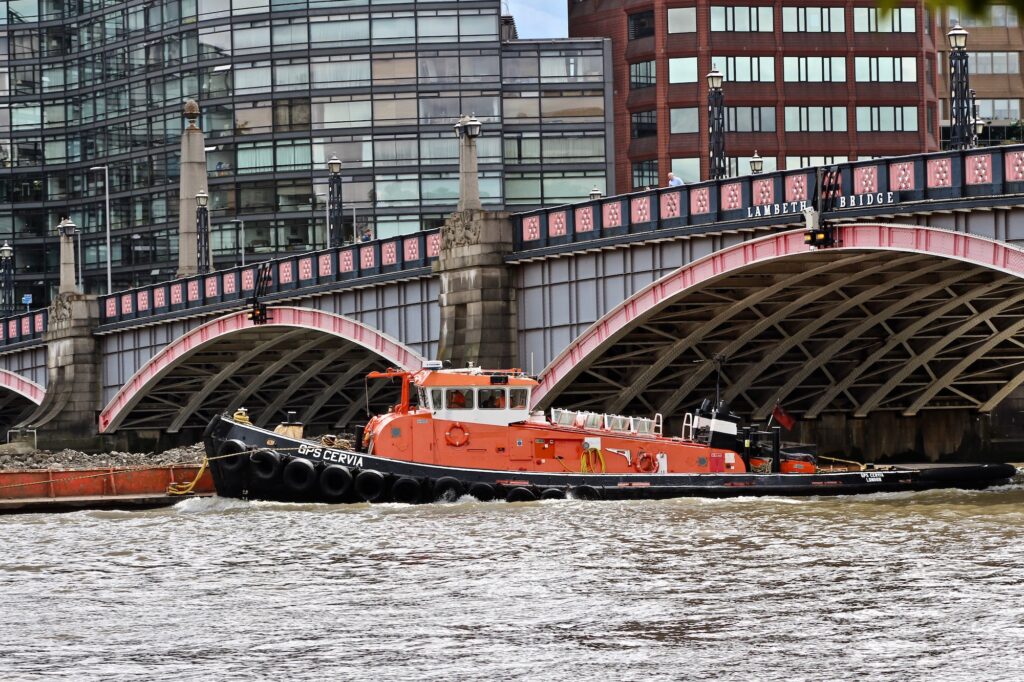

Another group of tugs, vessels in the fleet of GPS Marine Contractors Ltd., have had a different approach to their naming. The majority of them have names ending in “ia”. This idea is a legacy from the famous William Watkins Ltd. tugs which became part of a new company, Ship Towage (London) Ltd., on February 1st, 1950. In Thames Ship Towage 1933 – 1992 by J.E. Reynolds, the ‘William Watkins Ltd. Fleet List 1933-1950’ underlines GPS’s historic link with the company as back then names included: ‘Hibernia’, ‘Nubia’, ‘Scotia’, ‘Arcadia’, ‘Badia’, ‘Doria’, ‘Vincia’ ‘Muria’, ‘Fabia’, and ‘Cervia’. And John Spencer of GPS Marine explains that “many of the names you will see on our tugs were originally used by Watkins, now prefixed by GPS for reasons of corporate identity. But the tradition of ending names with an ‘ia’ still follows the same theme, such as for the tugs Iberia and Illyria”.

GPS tugs tow barges transporting tunnel segments upstream for sections of the tunnel lining of London’s new super sewer, the Thames Tideway project. Excavated tunnel material is loaded onto immense barges and towed downstream to East Tilbury in Essex. All this relieves London from much traffic and pollution. Their barges also carry aggregates to be used for making concrete, upstream to Hanson in Wandsworth.

Also involved in the transportation of material for London’s new sewer is the company Thamescraft Dry Docking Services, whose tug DEVOUT attracts quite a few *Likes* for my Twitter images. Spotting another of their tugs, DEVOTED, I was curious to find out if their names had any significance. Jack Deverell explained that “it’s just a play on our family name. The multicat ‘Jack D’ was named after me many years ago and the ‘Emilia D’, after my daughter.” These days ‘Emilia D’ is a familiar sight on the central London Thames.

Based in Greenwich for over twenty years the company operates one of London’s only remaining boatyards, carrying out half of all the annual maintenance work needed for London’s maritime tourism industry, and three-quarters of the Thames pleasure boat refit and maintenance work. In addition they deal with emergency repairs to vessels, piers, pontoons.

Some time ago, the London Port Authority had a tradition of naming a number of their tugs with the prefix ‘PLA’. They included this rather random selection of names: ‘Plagal’, ‘Plangent’, ‘Platina’, ‘Plateau’, ‘Plastron’, ‘Platoon’, ‘Plasma’, ‘Plankton’, and ‘Placard’ to fit their pattern. I came across ‘Plashy’ last year, delivered to the PLA in 1951, and after two changes of ownership she is now part of Thames Link Marine Ltd.

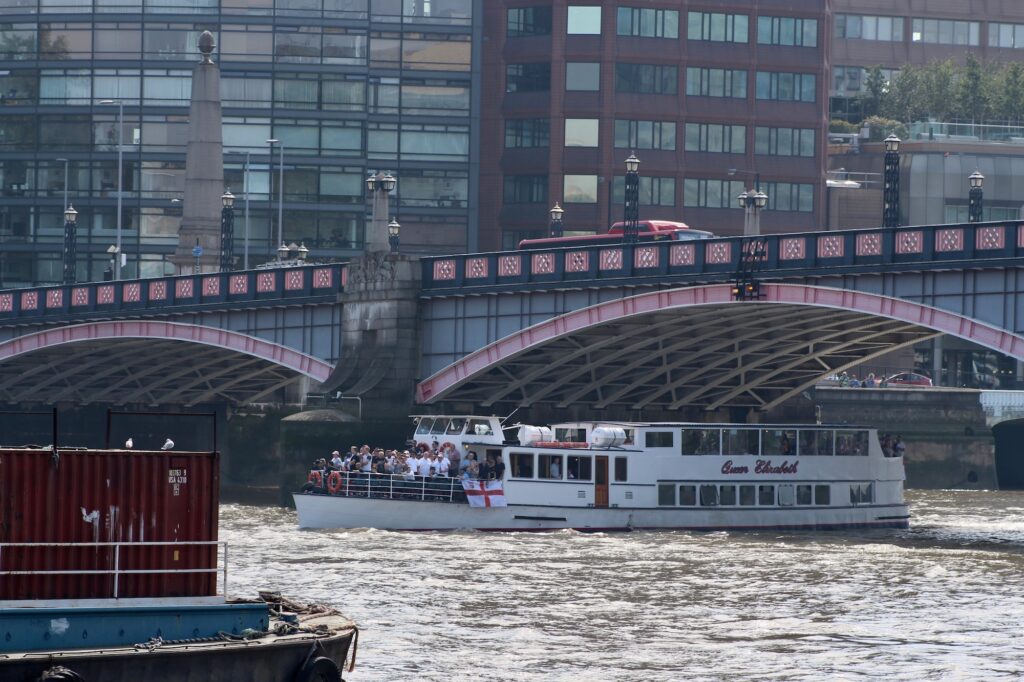

Boats of all kinds acquire their names for different reasons. Some to project a group or company image; some to honour a dignitary, a past hero, a benefactor, or a family member; and some are witty or whimsical. Ben, Waterman and Lighterman of the river Thames, told me that J.T. Palmer & Sons., at Gravesend, named three of their tugs ‘Nipalong’, ‘Nipaway’, and ‘Niparound’. However when the port authority of Auckland, New Zealand, was choosing names for their new electric tug, ‘Tuggy McTugface’ was deemed a step too far and excluded from the list.

Further Information

Detailed information on Thames Tugs: https://www.thamestugs.co.uk

The Liquid Highway: a rich resource for all kinds of information on the river Thames: https://theliquidhighway.co.uk/about/

A great Twitter feed for Thames news and historical photographs: @liquid_highway1

By clicking here you can see my earlier articles on Cory and GPS tugs.