In the late nineteenth century, distinguished art critic Sir Walter Armstrong gathered about four hundred etchings from various artists of the time and wove them into the narrative of his book The Thames from its Rise to the Nore, 1887.

Below are a few of my favourite images from the second volume covering the tidal Thames, etched at different times by different artists, not always named, which I have photographed and in some cases enlarged. They present an attractive and rather idealised picture of the River Thames but their detail is interesting and I have added a few remarks below some of them.

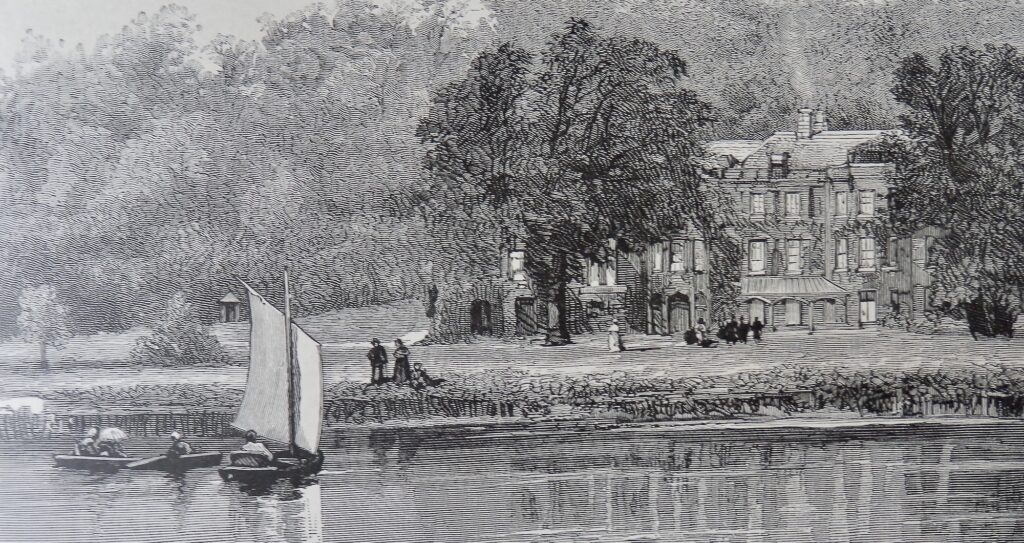

This much painted and photographed view from Richmond Hill was etched by A. Barraud. In 1902, after publication of Armstrong’s book, this view to the Thames across the pastures below, was protected by an Act of Parliament, and though other views in the country have been preserved by local planning legislation, the view from Richmond Hill is to this day, the only vista to have been so protected.

Richmond’s public park, Terrace Gardens, was created in 1887 from three eighteenth-century estates, one of which was the estate of Buccleuch, with its large house on the riverside and part of the gardens on the Terrace. Richmond Borough Council bought the riverside area in 1936 and Buccleuch House was demolished that same year.

Though this boatbuilder is not identified in the text, he represents the longstanding tradition of boatbuilding by Richmond Bridge still carried on these days by Master Boatbuilder, Mark Edwards, who established the Richmond Bridge Boathouses in 1992.

Armstrong describes Richmond Bridge as “a very modern institution. It is little more than a century since it was first thought of. The act for its erection was passed in 1773 before which the river had to be crossed in a boat.” Completed in 1777, it is the oldest bridge across the tidal Thames still in use.

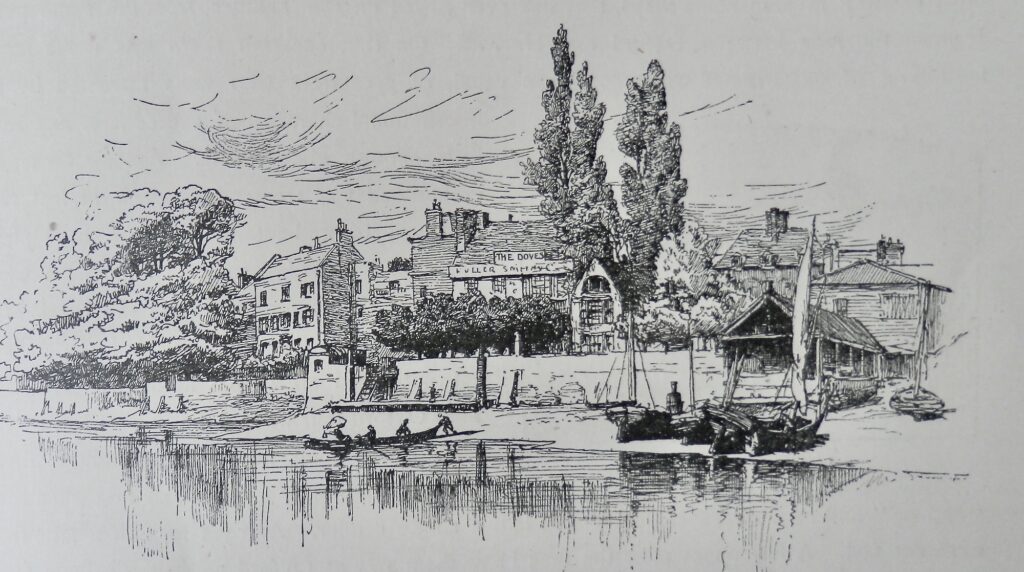

With a history dating back to the seventeenth century, The Dove, is still “a much-loved London pub catering for locals and visitors alike.” Among its famous regulars, including artists, composers and politicians, was King Charles II, who came here with Nell Gwynne.

The pub was one of the many buildings along the tidal Thames affected by the flood of 1928 which wreaked much havoc in Westminster and Pimlico, causing the drowning of fourteen victims trapped in their basements. The level of the flood is marked on a brass plaque in a “small space to the right of the bar, listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the smallest bar room in the world.”

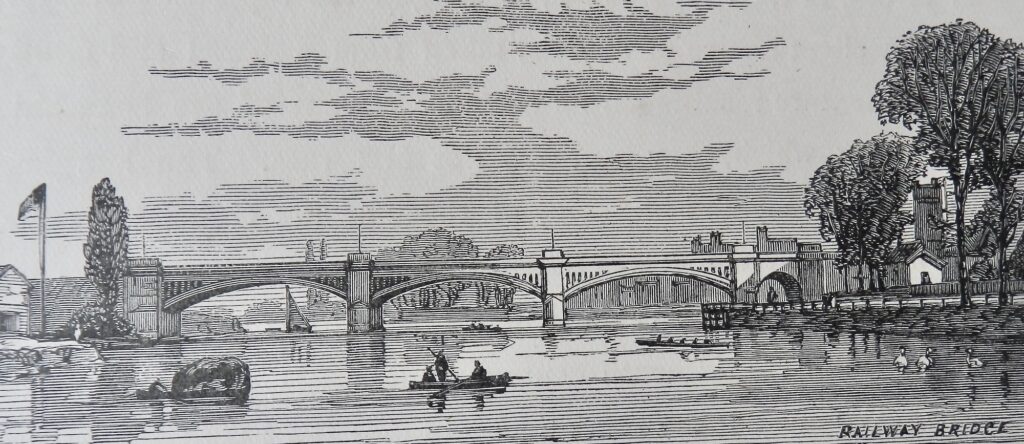

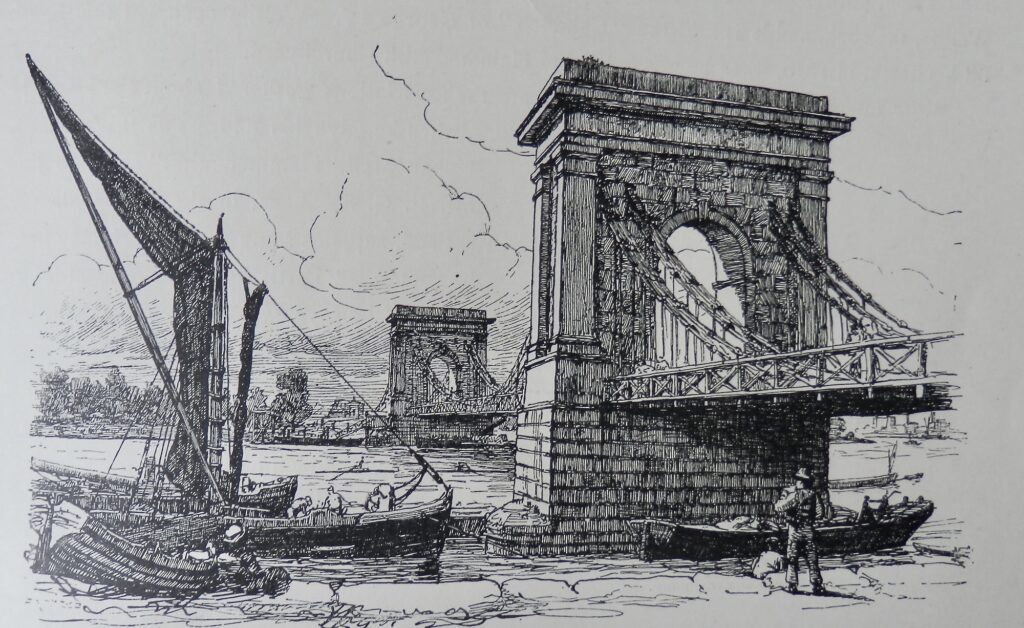

The old Hammersmith Bridge, the first suspension bridge to span the River Thames, was built in 1827, and Armstrong writes “so far as artistic design went, it was one of the best bridges on the Thames.” The present bridge that replaced it must have been under construction at about the time Armstrong’s book was being produced. It too is a suspension bridge, and was designed by Sir Joseph Bazalgette. It opened to the public in 1887.

As many of you will know, Hammersmith Bridge, was fully closed for safety reasons from August 2020 and eventually reopened to pedestrians, cyclists and river traffic in July 2021. For the latest information and background see: Hammersmith and Fulham Council

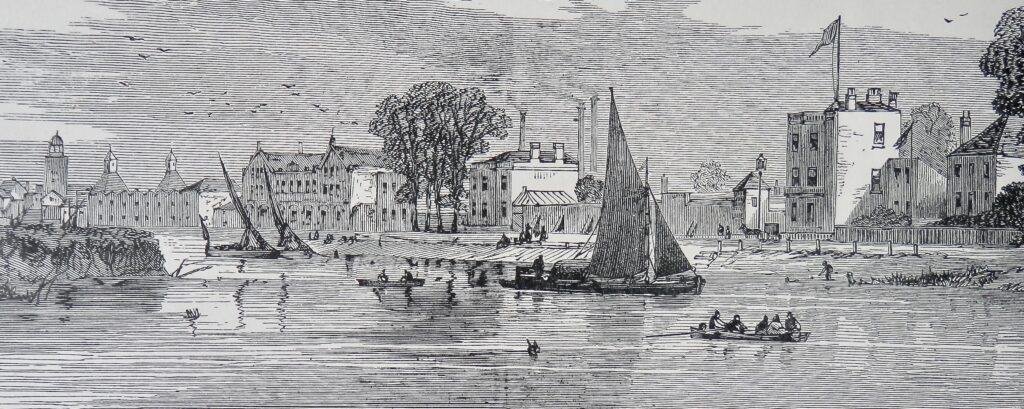

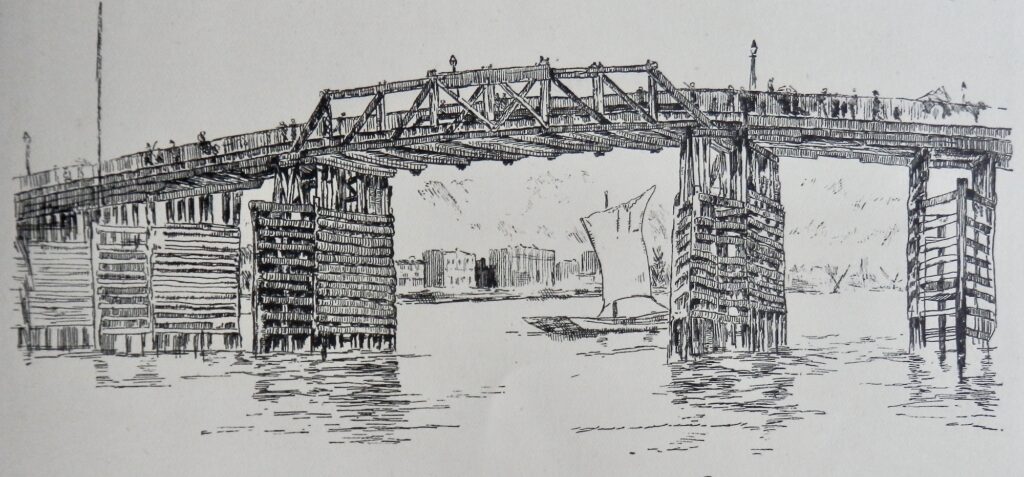

The old Putney bridge, opened in 1729, described by Armstrong as a “picturesque timber gangway, which called itself a bridge, was at last replaced by a fine new bridge”, designed by Sir Joseph Bazalgette, and opened in 1886.

Regarded as dangerous, old Battersea Bridge was the last surviving wooden Bridge over the Thames in London, and the patterns of its structure and reflections in the river, attracted the attention of several artists including Turner and Sell Cotman as well as Whistler.

The sharp-eyed among you might just be able to see the sign for Greaves’ Boatyard. It was the family boatbuilding business and home of artist Walter Greaves, who with his brother Henry became friends with James McNeill Whistler. Liss Llewellyn writes “Their father had been J.M.W. Turner’s boatman.” Greaves and Henry met Whistler in 1863, “introducing him to the sights of the River Thames, and becoming his studio assistants, pupils and close friends for over 20 years.” Greaves said that Whistler taught them to paint “and we taught him the waterman’s jerk”, which was possibly a “single oar scull or row.” However, the friendship did not end well. Whistler began to move in more fashionable artistic circles cutting out the Greaves brothers, and when Walter Greaves had an exhibition in 1911, Whistler’s biographers damaged his reputation by claiming that he had plagiarised Whistler’s work. By 1922 he was destitute and admitted into the London Charterhouse, and died in 1930. His work is not represented in this collection but you can see here, his best known picture: Hammersmith Bridge on Boat-Race Day c.1862.

From beneath the old Lambeth Bridge you can see the busy commercial shoreline at low tide with warehouses and the Palace of Westminster rebuilt by 1870, with a dominant Victoria Tower, which had been completed in 1860. However, the area was soon to be embanked as part Sir Joseph Bazalgette’s massive new sewer system for London. Dorian Gerhold writes that “By August 1872 the land, which now forms Victoria Tower Gardens, had been bought and cleared, and by 1877 the river wall had been built in line with the Terrace wall of the Palace of Westminster.”

The view from Richmond Hill to the River Thames, as mentioned above, was protected by an Act of Parliament in 1902, which still stands but Victoria Tower Gardens, created by an Act of Parliament (Section 8 of the London County Council Improvements Act) is not so lucky. Though the Act passed in 1900 required the gardens to be “laid out and maintained […] for use as a garden open to the public”, therefore prohibiting any construction, this much-loved, peaceful central London riverside park is under threat as the Government is now in the process of repealing the Act.

Sources and further information

Sir Walter Armstrong

Born of wealthy parents in 1850, Walter Armstrong was educated at Harrow and at Exeter College, Oxford, where reading only what interested him, he left with a pass degree. He spent his time studying pictures, art and literature. By 1880 he had become a distinguished art critic writing for a number of leading English journals and newspapers. It was during this period of his life that he gathered material, and wrote The Thames from its Rise to the Nore, published by J.S. Virtue & Co. Limited, London, in 1886-87.

In 1892 he was appointed Director of the National Gallery of Ireland and moved to Dublin. While he was there for over twenty years, he wrote a number of well-received books on leading artists including Reynolds and Gainsborough.

Images, quotes and text from:

Armstrong, Walter, The Thames from its Rise to the Nore, Vol II, J.S. Virtue & Co, Ltd., London, 1886

Architecture of the Palace of Westminster: Key Dates

Gerhold, Dorian: Victoria Tower Gardens – The prehistory, creation and planned destruction of a London Park, Dorian Gerhold, 2020

Pocock, Tom: Chelsea, The Brutal Friendship of WHISTLER and WALTER GREAVES, Hodder and Stoughton, 1970

The Dove, Hammersmith, history.

And thanks to Waterman and Lightermen Ben of The Liquid highway