The oldest church in the City, inextricably bound up with the Thames and the Port of London

Just a few steps away from the tourist-thronged Tower of London stands a church, founded in AD 675 as a chapel of the abbey of Barking, that is older than and steeped in as much history as its famous neighbour. And yet only a comparatively small number of visitors make it up to the South Entrance in order to explore within.

Despite standing by a busy main road, it’s the quietness that strikes you as you step inside, though from time to time there is the faint rumbling beneath your feet of a nearby underground train. Yet its situation by the Thames, with the parish’s southern boundary being in the middle of the river, has naturally had an important effect on its life. And the Mariners’ Chapel in the south aisle reflects this.

The altar, panels, model ships, memorial plaques, and stained glass windows all bear witness to the church’s links with the sea, the river, and the Port of London. The Custom House, quays and docks were on the riverside close by.

The wooden screen behind the altar commemorates the links between the Port of London Authority and All Hallows by the Tower. In the centre of the altar a candle burns for “all seafarers who are in danger or distress”, and a prayer for all those, whoever and wherever they are, “exposed to the many dangers of the deep”.

The crucifix above the altar was made from a piece of wood from the Cutty Sark and the ivory figure of Christ is believed to have come from the captain’s cabin of the Spanish Armada’s flagship.

Looking around the chapel you will see several intricately made model ships, hanging from arches, placed on furniture or in cabinets. Over the years they have been given to the church as ex votos, symbols of thanksgiving, memorials, or simply by boat builders as they moved premises.

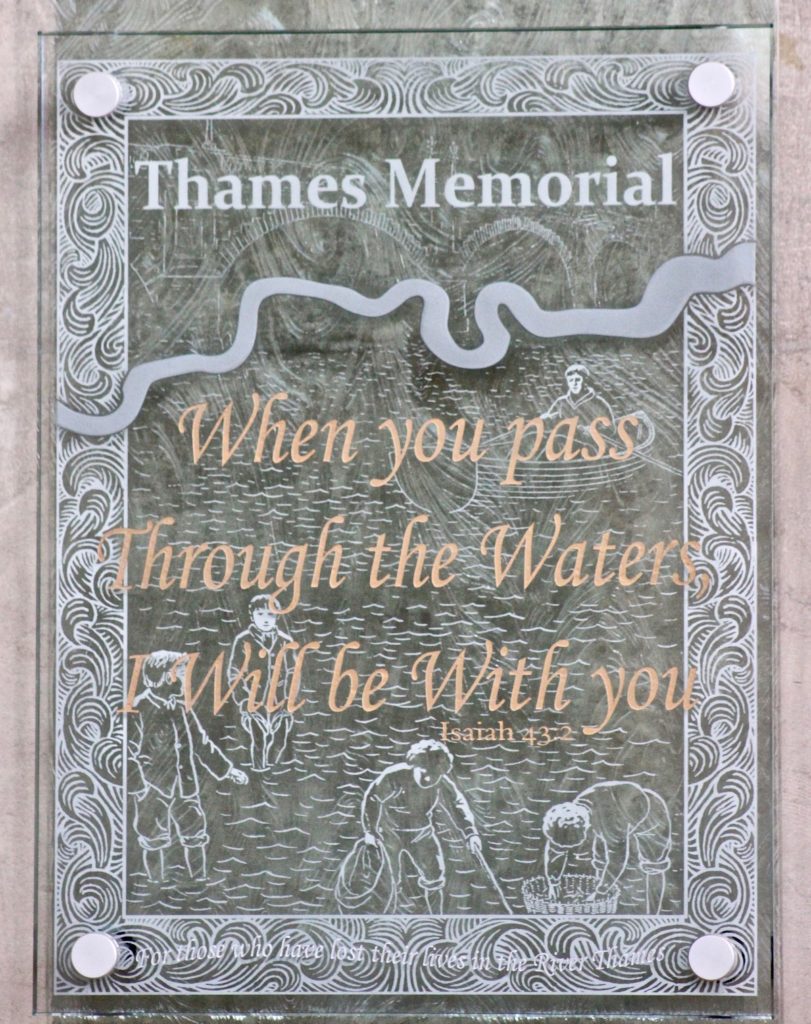

There are a number of poignant memorials, around the church, in the chapel and in the Crypt Museum, including one for HMS Hood, sunk during the Battle of Denmark Strait in the Second World War, with the terrible loss of 1,415 lives, leaving only three survivors. Also on display is the Maritime Memorial Book, established by the Maritime Foundation in 1987 recording the names of those who “have no grave but the sea” to which names can still be added if you search their site. And on June 25, 2019, a Thames Memorial by Clare Newton was dedicated in a moving service to all those who have lost their lives in the Thames.

The church was bombed on two occasions during the Blitz: first the east end was badly damaged by a bomb in December 1940, and three weeks later the whole building was gutted by incendiary bombs, leaving only the tower and outer walls standing. However, All Hallows was fortunate at this time to have the Reverend Philip Thomas Byard Clayton, nicknamed affectionately ‘Tubby’, as its vicar.

An army chaplain during the First World War he had teamed up with another chaplain, Neville Talbot, creating Talbot House as a refuge for battlefront soldiers, an alternative to the temptations of the town of Poperinge in Belgium, where they could spend their leave. It was known as Toc H, which grew into an “international philanthropic organisation promoting ideals of service, comradeship and reconciliation.” After Clayton’s installation as Vicar of All Hallows in 1922, the church became the guild church of the movement.

On the very day that the church was bombed Clayton at once declared that it should be rebuilt. His enthusiasm and powers of persuasion had a strong impact. The foundation stone was laid by Elizabeth, the Queen consort of George VI, in July 1948. There followed practical donations in the form of various building materials and financial support from all over the world, and the church was re-dedicated in 1957.

During all this time Clayton remained vicar of All Hallows by the Tower and also chaplain to the Port of London Authority. A report in The Guardian on August 4, 1947, describes how he kept “a close eye on anything happening on the Thames” and highlighted his concern about accidents on the Tower beach. Bathing was allowed “when the tide is safe” and there were wardens to watch the children but several accidents had taken place when the beach was closed. He was also worried about the dangers posed by the ‘Iron Gate Stairs’ there. As a special precaution for the August Bank Holiday that year, Clayton arranged for a “voluntary patrol of men” to watch the Stairs from a boat.

The stained glass windows, especially in the south aisle, bear witness to the church’s close association with the sea and the river Thames. As all but two of the seventeenth-century stained glass panels were destroyed during the Blitz, the beautiful stained glass windows you can now see were all made post war. Several of them were donated by the City of London Livery Companies associated with the church.

The church’s close links with the river can be seen again in the annual ceremony of Beating the Bounds. This is a tradition dating back to medieval times, when parishes processed around their boundaries, beating boundary markers with sticks to mark out their territorial limits. The added interest to the All Hallows’ ceremony is that part of their boundary runs along the middle of the Thames and the beating party “made up of the clergy and the Masters of the livery companies associated with the church, go out on the river in a boat to beat the water with their canes before returning to shore and continuing around the rest of the parish.”

In writing this piece I have concentrated on All Hallows’ close links with the Thames, the Port of London and shipping world-wide. However, there is much more to discover including its architectural history, which dates back to Roman times; its strong association with the Tower of London; its role in the temporary care of bodies of high profile prisoners beheaded on Tower Hill – a list of confirmed executions can be seen here; and its links with America, which will be of particular interest to my American readers.

Admiral Penn, father of William Penn who founded the colony of Pennsylvania, was also a Member of Parliament at the time and helped to save the church during the Great Fire of London in 1666 by directing some of his men from a nearby shipyard to create firebreaks to protect both St Olave, Hart Street and All Hallows, by demolishing nearby buildings. His son William was baptised in the church and educated in the church school before setting off to America. A further link is that with John Quincy Adams, sixth President of the United States, who married Louisa Catherine Johnson in All Hallows on July 26, 1797.

At ease with its eventful past, wide international links, and place in the fabric of both the City of London and the country, All Hallows welcomes visitors to its services, those in search of history, and those who seek space for prayer and quiet contemplation. It is today a modern, “active and inclusive Christian community”, and its associations and ties with the river Thames remain as strong as ever.

Using the link highlighted here, you can find out more about the history of All Hallows by the Tower