Set in Victoria Tower Gardens, next to the Houses of Parliament, The Buxton Memorial commemorates one of Parliament’s most important Acts: “The Emancipation of Slaves, 1834”, which came into force that year. It is dedicated principally to Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, the leading Member of Parliament, who ensured the passing of the Act through all its stages.

Building of the Memorial

Commissioned by Charles Buxton, MP, and dedicated to his father Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, the Buxton Memorial Fountain, as it was then, was first erected in 1866 at the corner of Great George Street, leading from St.James’s Park into Parliament Square.

It was a flamboyant example of Neo-Gothic architecture but by 1949, after the austerity of the Second World War, the ground where it stood was incorporated into the new road design for Parliament Square. Rather than destroying the monument, as some would have wished, tastes and fashions having changed, it was dismantled and put into store to be rebuilt at a point in the future as its conservation had been assured by an Amendment to the Parliament Act in 1949. An engraved stone on the west side of Parliament Square, leading to St. James’s Park, now marks the place and dates of where it originally stood.

In 1955 the fate of the Buxton Memorial, already in storage for six years, was brought to the attention in the House of Commons where Members debated “the proposal made by the Minister of Works for re-erecting the Buxton Memorial Drinking Fountain.”

The Minister of Works, Nigel Birch, having agreed that it would be wrong to reinstate the memorial in Parliament Square, and having refuted some of the arguments against its being completely redesigned put forward the arguments of the Anti-Slavery Society saying: “It ought to be re-erected near the Palace of Westminster because it was in the Palace of Westminster that the struggle was fought and won.” He added the Society’s point that it would be “strange if in Parliament Square we had a statue of Abraham Lincoln, the emancipator of the American slaves, while our own emancipators, who performed their task earlier and without the shedding of blood, were not commemorated near where that struggle was fought.”

Nigel Birch went on to say that two previous Ministers of Works had given “conditional undertakings that the fountain would be re-erected in Victoria Tower Gardens.” And the timing was good, for proposals which had been announced and approved for the re-design of Victoria Tower Gardens in 1955-6 provided the opportunity to carry out those undertakings. With the support of others, he won the debate: “That this House approves the proposal made by the Minister of Works for re-erecting the Buxton Memorial Drinking Fountain, a copy of which proposal was laid before this House on 15th November.” Hansard, November 30, 1955.

Construction

Octagonal in shape, and roughly twelve feet in diameter, its intricate structure is made up of limestone, grey and pink granite, grey and red sandstone, red marble, wrought iron, and terracotta. Sculptures of dragon-like creatures lunge outwards and, set between the arches, is a series of legend-inspired mosaics. The spire is timber framed and clad with enamelled metal work. It could almost be a pattern book for Neo-Gothic design.

Historic England, listing the memorial as Grade II*, puts the date of its creation as 1864-6. “Designed by Samuel Sanders Teulon, with what appears to have been a considerable creative contribution from Charles Buxton.”

The tablet at its base reads:

“Erected in 1865 by Charles Buxton MP in commemoration of the Emancipation of Slaves 1834, and in memory of his father Sir T. Fowell Buxton and those associated with him: Wilberforce; Clarkson; Macaulay; Brougham; Dr. Lushington and others.”

Copyright © 2019 Alamy Ltd.

The missing figures

Looking at the image above you can see five of the eight small bronze figures, by Thomas Earp, that originally stood at the base of the spire. The Thorney Society explains: “They represented past rulers of England including Britons, Danes, Saxons and Normans and ended with Queen Victoria.” Some of them were stolen in 1960, the rest in 1971. Finally replaced in 1980, these were also stolen so that their plinths now remain empty.

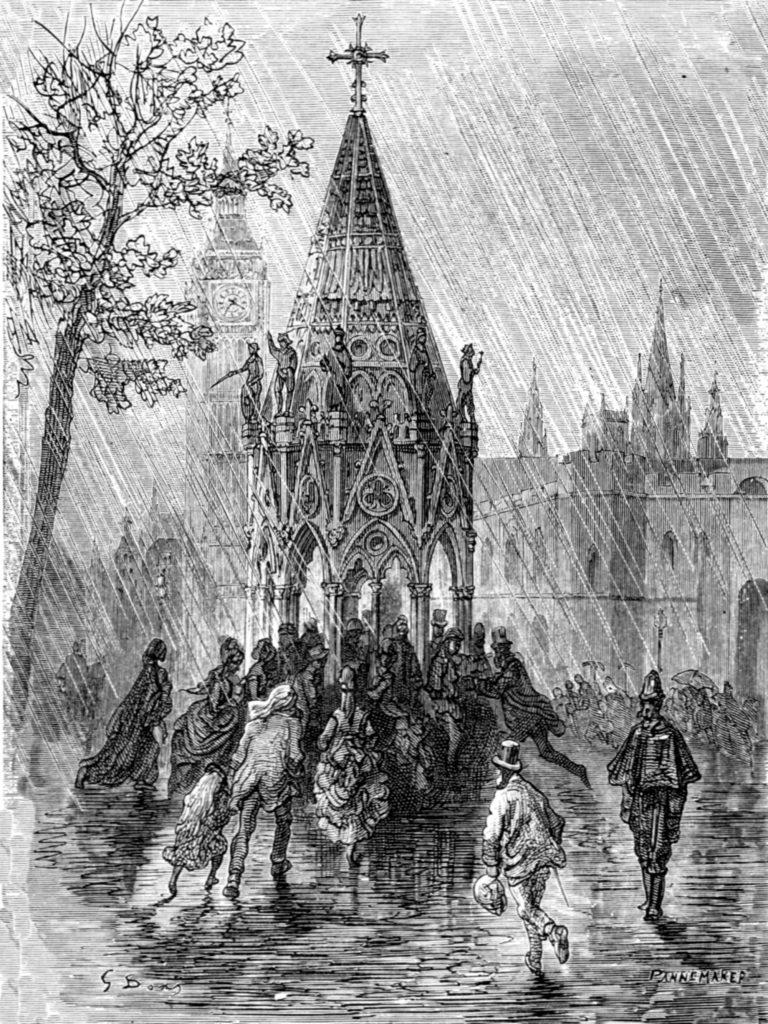

Gustave Doré

French artist and printmaker, Gustave Doré was a famous and highly successful, prolific book illustrator. In 1869 he set out to explore London, in all its aspects, with his friend, British journalist William Blanchard Jerrold. Many of his engraving feature life on and around the Thames.

The Conservation, 2025

The recently restored Buxton Memorial Fountain was upgraded from II to II* in 2007 and listed for the following main reasons:

“It is an unusual and exuberant example of the work of S. S. Teulon, in association with Charles Buxton, and the lavish and imaginative use of materials, especially in its enamelled roof.

In May 2024 specialist contractor Stonewest was awarded the contract by The Royal Parks, to undertake the conservation of the memorial. A statement on the company website explains:

“We were delighted to complete the conservation work to the Grade II listed Buxton Memorial Fountain, situated in the Victoria Tower Gardens in London’s Westminster. On behalf of The Royal Parks and working with heritage consultant Purcell, we carried out considerate stonework and decorative metalwork repairs to the Memorial, as part of the long-term management of this historic asset.”

Removal of the scaffolding

A closer look after the conservation work

The Mosaics

There are several purely decorative mosaics dotted around the memorial as well as a number of representative scenes.

Opinions differ as to what each of the figurative mosaics represent. One suggestion is that they are mostly inspired by the fables of Aesop. What I would recommend, if you would like to study them closely to see how many you can identify, is to bring a pair of binoculars.

Bob Speel notes that: “One of the mosaics is worth closer attention, it depicts an enslaved person supposedly being emancipated, chains broken off him.” He adds that it is difficult to see all the details, and suggests that “another interpretation could be the aggressive violence inflicted upon enslaved people.” The figure on the bottom left, appears to be praying.

Details of the Spire

Regular local users of Victoria Towers Gardens, having watched the progress of work on the Buxton Memorial over the past couple of years, have recently delighted in its gradual de-scaffolding. Visitors, cameras in hand are fascinated by its bright complexity, and, those who seek further to discover its purpose, learn about the commemoration of the passing of the The Emancipation of Slaves Act, 1833, which came into force in 1834.

After its removal from Parliament Square in 1949, it was reassembled in Victoria Tower Gardens in 1957. It was thought appropriate for it to be placed there, “because of the deep connection to Parliament which, as one observer noted ‘cleansed the country of its terrible inheritance of the slave trade’. This is one of the reasons The Thorney Island Society “has advocated that the Holocaust Memorial be sited somewhere else nearby rather than in Victoria Tower Gardens because there is no direct link with Parliament as there is with the Buxton Memorial.”

There is also the view that the memorial was carefully positioned so as to echo, unimpeded, the architecture of the Palace of Westminster.

Sources and further Information

Debate in Parliament on the reinstatement of the Buxton Memorial Fountain. Hansard

Historic England Buxton Memorial Fountain, Victoria Tower Gardens.

History of Parliament: 1833 Slavery Abolition Act

LONDON. A Pilgrimage” by Gustave Doré and Blanchard Jerrold.

Specialist Contractor: Stonewest

Speel, Bob, article The Buxton Memorial Fountain

The Noel BuxtonTrust charity

The Thorney Island Society ‘Thorney Tales (18) The Buxton Memorial Fountain’.

The Victorian Web ‘The Buxton Memorial Fountain’.