…on the foreshore of Victoria Tower Gardens

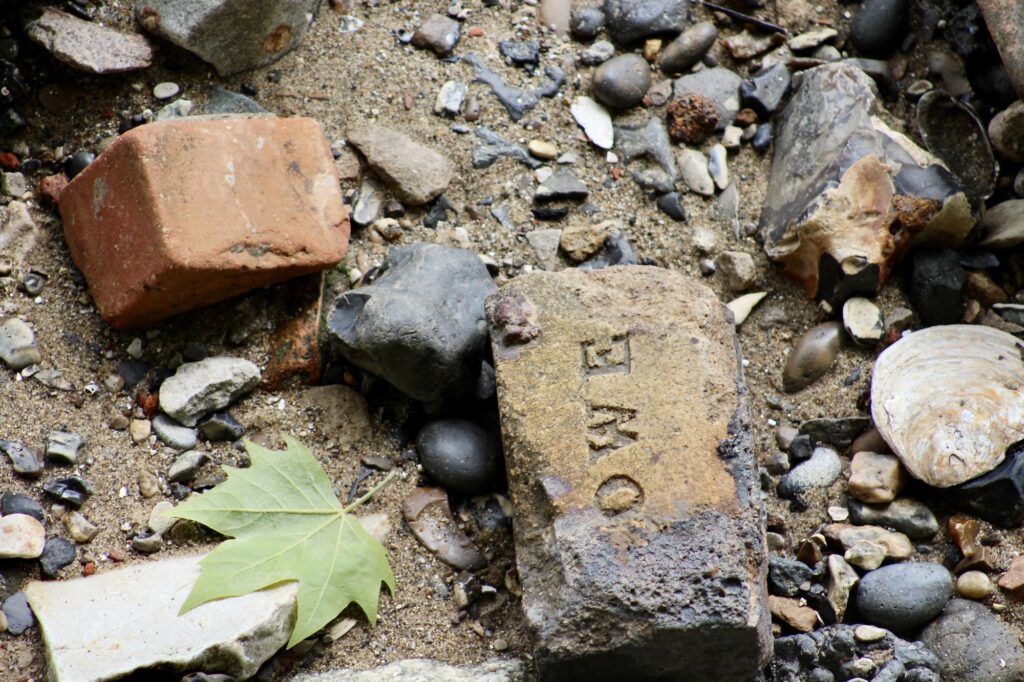

Dr. Dorian Gerhold, distinguished London historian, knows all there is to know about Victoria Tower Gardens. In his meticulous study in 2020 he wrote: “The area, now the gardens, was reclaimed from the Thames in the medieval and later periods, forming at first a part of the Palace of Westminster and the estate of Westminster Abbey.”* He adds that “For more than 250 years afterwards it was occupied by a variety of wharves and houses”, none of which exist today. But look over the embankment wall at low tide and you will see a mass of mingled traces of the past: multicoloured fragments of history.

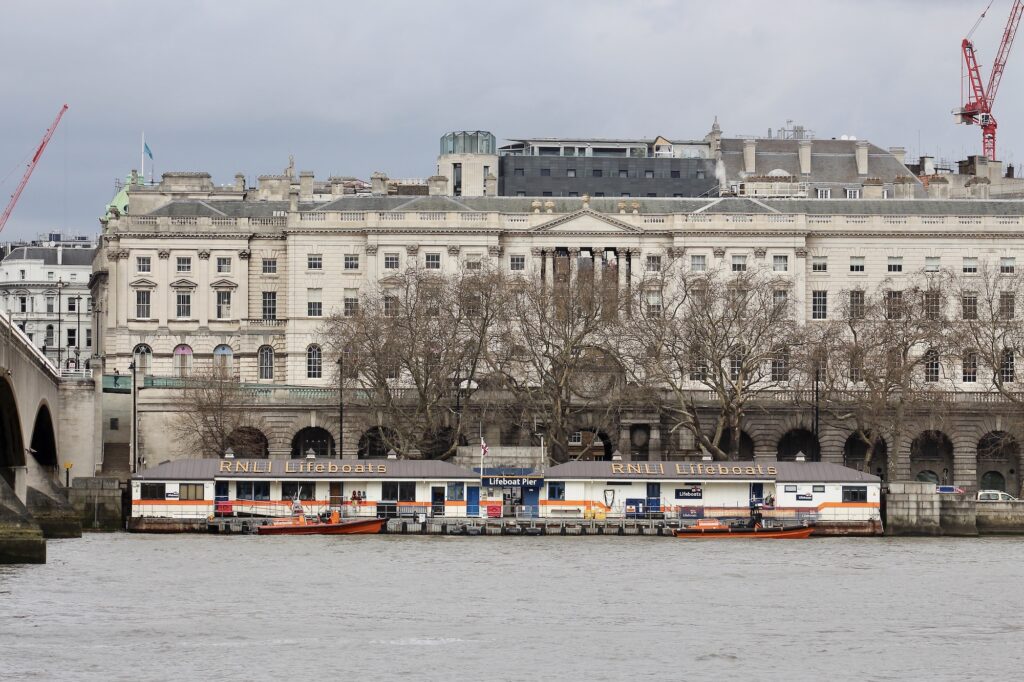

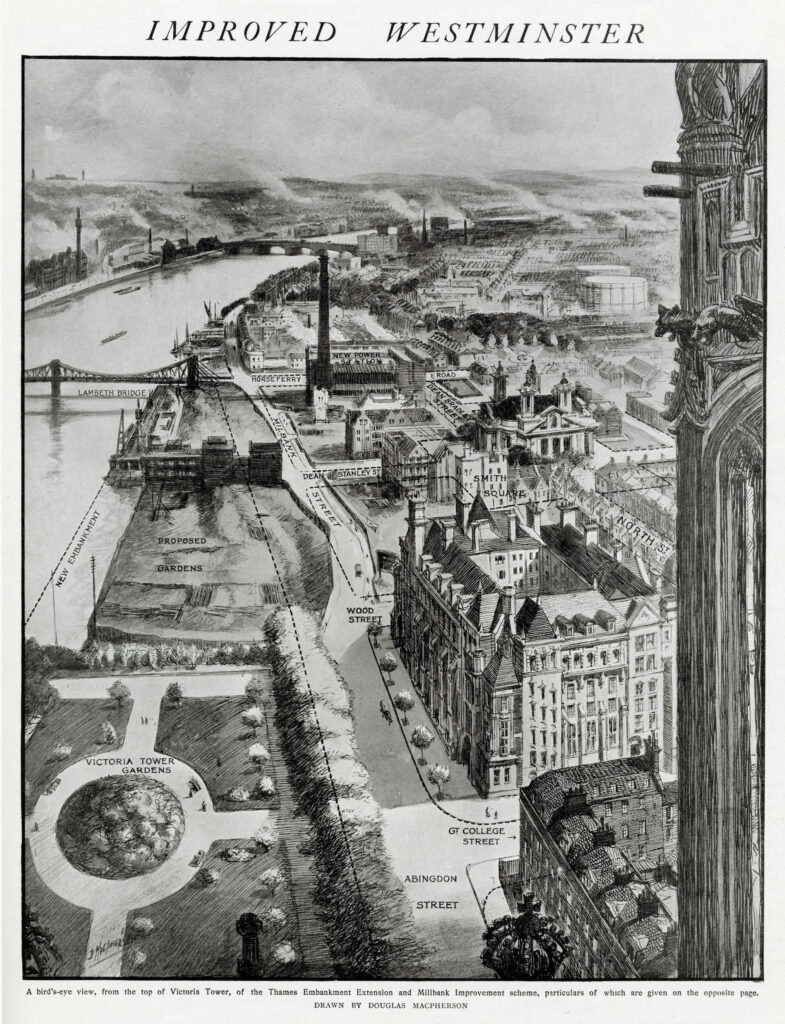

Both William Strudwick’s photograph above and the drawing below by Douglas MacPherson in the Illustrated London News, 1911, of the then existing Victoria Tower Gardens with work in progress, show the extent of construction there has been on the site. But further research has taken us back in history.

Work to the area now covered by Victoria Tower Gardens was along the river from the already established garden directly below Victoria Tower to Lambeth Bridge. It was part of a scheme known as the “Thames Embankment Extension and Westminster Improvements at Millbank.” In the image above there is a dotted line illustrating the proposed building of an embankment wall in line with the Palace of Westminster, taking in part of the foreshore. This was eventually built by 1914 when the enlarged Gardens were opened to the public.

In 2017 a survey undertaken by Sumo Services reported, though none had yet been recorded, that there was the “potential for finds from the prehistoric period to the Roman and early medieval periods […] as there was evidence of Roman and Saxon activity within 250 metres of the site.” They concluded that “there are extensive examples of development on the site throughout the post-medieval period and remains relating to a wide range of riverside and industrial activities are likely to have survived over much of the area.”

However, in 2013 members of the Thames Discovery Programme were first invited by the Parliamentary Estate to record “the scatter of medieval and post-medieval moulded stone revealed by World War II bomb damage.”

Among the finds were: “a silver Elizabethan half groat and a sixpence; a royal farthing of James I; a late 17th to mid 18th-century tin alloy and glass cufflink; a complete lead alloy porringer handle; a late 17th-century tin ‘American plantations token’; and an 18th-century cloth seal.”

Looking over at the stones and rubble of the past from the embankment above is an escape, an appeal to the imagination, without the danger of falling over or being cut off by the tide. Experts will know far better than I what these photographs might represent. Some objects stay firmly in place, resisting the strong tidal currents, others are constantly moving, being exposed or worn down.

There are strict rules in place for mudlarkers from Teddington Lock to the Thames Estuary as to where they are allowed to search the Thames foreshores. For anyone who is not familiar with them see here. Its proximity to the Palace of Westminster means that the Victoria Tower Gardens’ foreshore is a sensitive security area, most of which is out of bounds, only accessible by special permission, usually as part of an organised group.

On March 16, 1941 during the Blitz, a Nazi bomb exploded on the embankment wall breaching it so far down that had not the tide been out, the whole area would have been inundated. London owes its escape from such a disaster to Sir Thomas Peirson Frank, who had had the foresight to plan for such an eventuality, and repairs were swiftly carried out, first with sandbags and then with reinforced concrete still plainly visible today. Many remnants of the orignal wall are still scattered below.

In his book Victoria Tower Gardens […] Dorian Gerhold writes of the many industrial constructions that existed over the years which were eventually cleared in stages to make way for the gardens. They included: wharves handling stone, coal, timber, lime and sand. There were cement, flour and oil refining works, corn merchants, a sailmaker, an ice storing business, and many others.

A report prepared for Westminster City Council by London Parks & Gardens Trust in January 2019, states that the location of the wharves marked on contemporary maps “gives some indication of the unstable ground conditions found on site today as the majority of the Gardens is ‘made-up’ ground.” And it’s clear that elements of these can also be found on the foreshore.

The force of every ebb and flow of the tide changes patterns on the foreshore, though many of the larger pieces remain more or less in place despite their gradual erosion.

Staring at these stones, shells and bones it’s possible to imagine one of those computer reconstructions where fragments are lifted, whirling upwards to reassemble into conceptual shapes of their past…

The foreshore is littered with ever smaller vestiges of the past, ground down little by little by attrition until reduced to sand.

“We are but dust our days are few and brief, like grass, like flowers, blown by the wind and gone forever.”***

Yet while we can, it is satisfying looking down at the foreshore and trying to feel something of the lives of those who passed this way before us.

Sources and further information

*Gerhold, Dorian: Victoria Tower Gardens: The prehistory, creation and planned destruction of a London park, 2020.

Sumo Services Ltd, Survey of Victoria Tower Gardens.

The Thames Discovery Programme with report on Victoria Tower Gardens here. Also article by Nathalie Cohen, March 21, 2018.

Victoria Tower Gardens update, September 5, 2021.

In order to mudlark or metal detect on the Thames foreshore you must hold a valid permit from The Port of London Authority. No new permits are being issued at the moment due to over-subscription, though current permit holders can renew.

However there are tours organised by the Thames Explorer Trust.

***Psalm 103, v. 14-16

Images

‘Improved Westminster, 1911′ and Lambeth Palace, 1860’ from Millbank, 1860, courtesy of Mary Evans Picture Library

**William Strudwick: photograph, *scanned by Leonard Bentley.

All other images © Patricia Stoughton