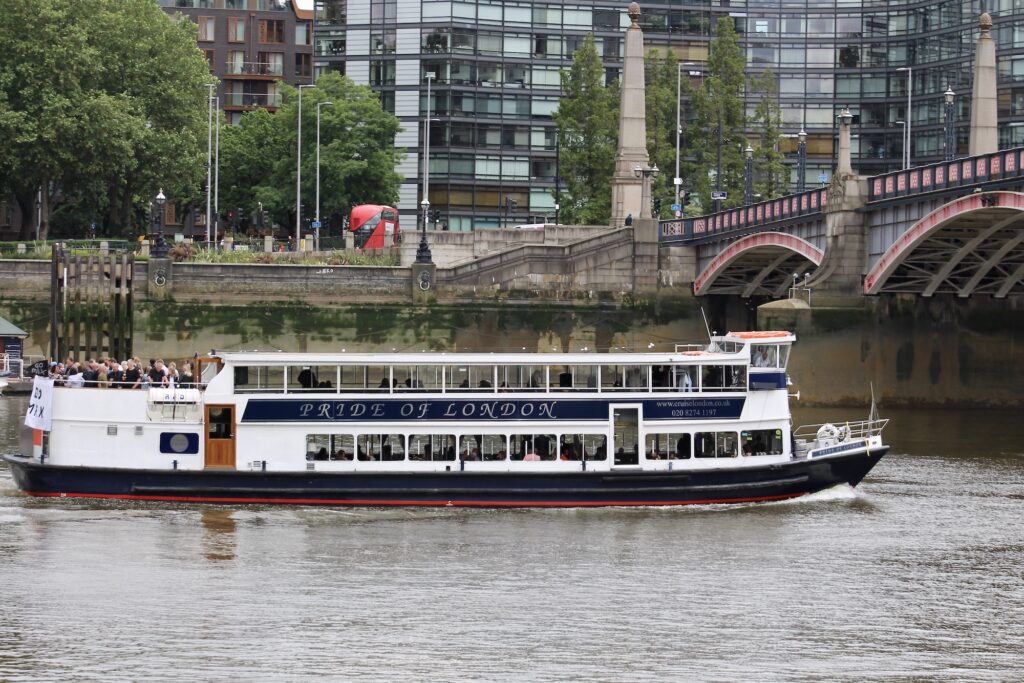

…from Lambeth Bridge

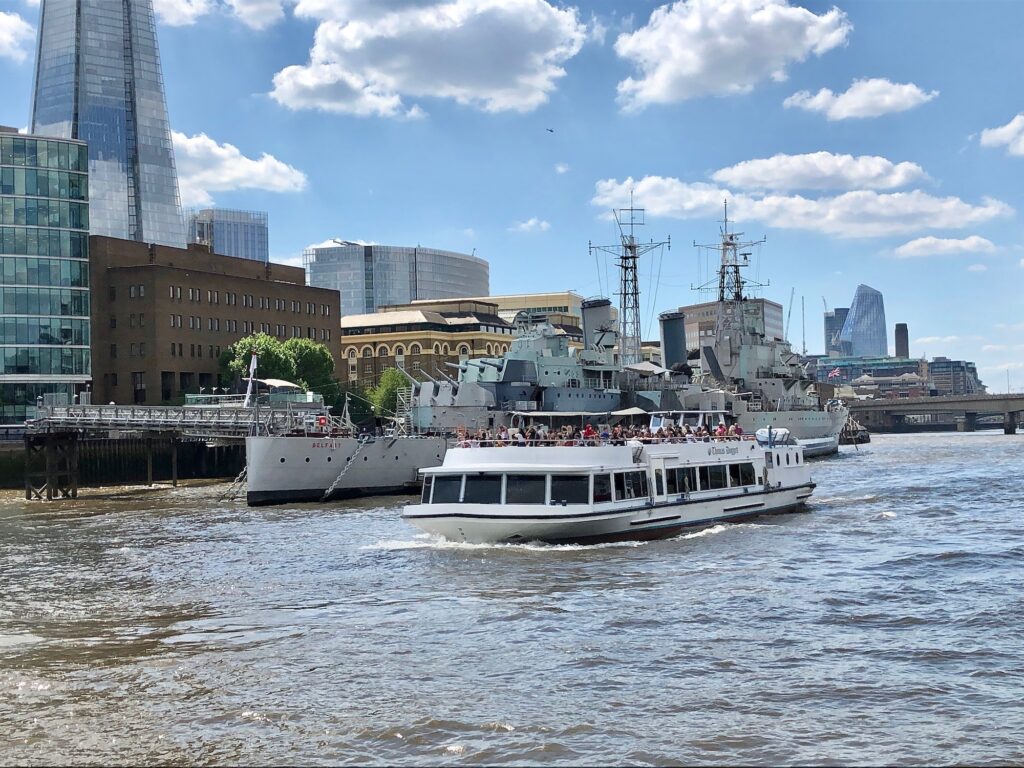

Walking by the Thames between London Bridge and Cadogan Pier on the morning of Friday June 25th, you might have noticed a little more activity than usual on the river. What you would have seen were the four competitors rowing single sculls in the Doggett’s Coat and Badge Wager, an annual contest that has been in continuous existence on this stretch of the river since 1715. And preceding, or following them were support boats, press boats, and party boats of invited family, friends and colleagues.

The race was originally run between two Thames-side pubs: from the Old Swan Tavern at London Bridge to the Swan Inn at Chelsea. The route is now four miles seven furlongs long, from London Bridge to Cadogan Pier. The record for the fastest time to complete the course, 23 minutes and 22 seconds, chalked up in 1973, is still held by Bobby Prentice, Bargemaster to the Fishmongers’ Company, and now race umpire. And it is the Fishmongers’ Company, who fulfilled a promise to Thomas Doggett to make sure that the race took place every year after his death. However, since 2019 the Company of Watermen and Lightermen have taken over the management of the race and are now in partnership with the Fishmongers’ Company.

First raced in 1715, the Doggett’s Coat and Badge Wager came into being as a result of Irish actor Thomas Doggett’s gratitude to the Thames Watermen of the day. And legend suggests that it was for one of two reasons. According to the ‘History of the Wager’ on the site of the Company of Watermen & Lightermen, the first was that “while returning home from the theatre one night he fell into the river and was rescued by a waterman.” The second was that conditions on the Thames were so bad that among the watermen only “one young, newly appointed waterman agreed to row him across the Thames, and did so safely.” Neither of these versions can be verified but what is documented is “that he organised the race himself until his death in 1721”, and from then on it took place every year according to instructions he left in his will. Six races were postponed from 1915 – 1919 during the First World War but rescheduled over two days in 1920. Races were held up again during the Second World War but those missed took place over two days in 1947, so that there is an unbroken list of yearly winners since the creation of the competition. It was then the covid pandemic that caused a third postponement, so the race this June, was in fact the one due in 2020. The 2021 race will take place on September 8th.

The Wager is open to watermen and lightermen in the first year of what is known as their ‘freedom’, after completing their apprenticeship, and they must be aged between 21 and 27. They are allowed up to four tries for the prize, which is a traditional waterman’s coat “crimson red with a silver arm badge depicting Liberty, the horse of the House of Hanover” in honour of the accession of George I to the throne in 1714. It’s a striking combination, and Doggett’s winners are proud to own and wear it.

The four competitors on this occasion were: James Berry, captain with Thames Clippers, dressed in white; Max Carter-Miller, of Thames Marine Services, in black; Coran Cherry of Thames Clippers in pale blue; and George Gilbert, of Capital Pleasure Boats, in red.

The photographs of the contestants below were taken from vantage points on Lambeth Bridge so as to capture their approach from Westminster Bridge. I have grouped pictures of their supporting boats with them, though some went on through to Cadogan Pier ahead of the race. The photographs at the end of the piece were kindly lent by the Port of London Authority and Ben of Liquid Highway.

The Doggett’s Coat and Badge Wager often created a great deal of public interest in London and was regularly reported in some detail in the press. An account in The Times on August 2nd, 1864 described the scene: “…thousands of spectators, afloat and ashore, the banks, bridges, and craft in the whole of the long course between London-bridge and Chelsea being densely crowded with persons anxious to view a part of the race.” There was a great number of tugs, and the river literally swarmed with boats of every size, including steamers and barges.

Reports also carried details of the races themselves with navigational difficulties, tactics, and changes in the fortunes of the contestants, particularly dealing with the currents around the bridges, swifter and more complex since the construction of the central London embankments between 1864 and 1874.

There is a good report on this year’s race with photos by Tim Koch on Hear The Boat Sing.

In 1938, there were only two competitors in the race and The Times report that year mentions how completing the course could once take nearly an hour and a half but that things had speeded up “now the race is rowed on the flood, instead of against the ebb, and in outriggers instead of old heavy wherries – the working boats in which the competitors plied for hire.” With the race only rowed on the flood tide, the times became much quicker. James Berry won this race in a swift 25 minutes 31 seconds but Bobby Prentice’s record still holds good.

Last year the race was won by Patrick Keech, from Hextable, near Dartford, after a close ‘fight to the finish’ with this year’s winner, James Berry. And among previous winners are Sean Collins, chief executive and co-founder of Thames Clippers, who won in 1990, and Michael Russell of the Port of London Authority, who won in 1997.

The race was umpired by Bobby Prentice, whose boat SARAHANNE remained close to the contestants. It was followed by Thames Limo’s BOURNE carrying representatives of the Company of Watermen and Lightermen; WINDRUSH 46, carrying several press photographers; Port Health Authority vessel LONDINIUM III; and the Port of London Authority vessel BARNES.

Having finished the tough course, the contestants celebrate together.

The race is a real test of determination and strength and the rowers need to have a good knowledge of the currents and flow associated with every twist and turn of the river and each particular bridge. When the race first began, there was just one, London Bridge, now there are eleven. Earlier races could take place against against the tide but with the embankment of the central London Thames and the consequent increase of tidal flows, they have have been rowed with the tide since 1873.

Sources and further information

The Company of Watermen and Lightermen of the River Thames

Doggett’s Coat and Badge Race

Hear The Boat Sing

London Metropolitan Archives

Thames Limo

The Liquid Highway

The Port of London Authority

The Thames Festival Trust

Notes

*The race on June 25th was the race postponed from 2020 and the 2021 race will take place on September 8th. See the countdown here: The Doggett’s Race

*For those unfamiliar with these terms: Lightermen carry cargo from larger moored ships to docks, and Watermen carry passengers in a variety of boats.